Saudi Arabia welcomed 100 million tourists in 2024. Read that number again, because it’s genuinely staggering. That’s more visitors than Italy. It’s comparable to Spain. It’s approaching France’s numbers. And ten years ago, Saudi Arabia issued virtually zero tourist visas. The kingdom didn’t want tourists. Tourism was forbidden, period.

Now they’re building mega-resorts, hosting Formula 1 races, and marketing aggressively to Western travelers. Saudi Arabia, along with Jordan, Oman, and the UAE, is attempting one of the most ambitious economic transformations in modern history: pivoting from oil dependence to tourism. They’re investing hundreds of billions in infrastructure, marketing, and image rehabilitation. And against all expectations, it’s working. Tourists are actually coming.

The question is whether this transformation is sustainable, or if it’s an expensive mirage built on oil money that will evaporate when the contradictions become impossible to manage.

The $800 Billion Gamble

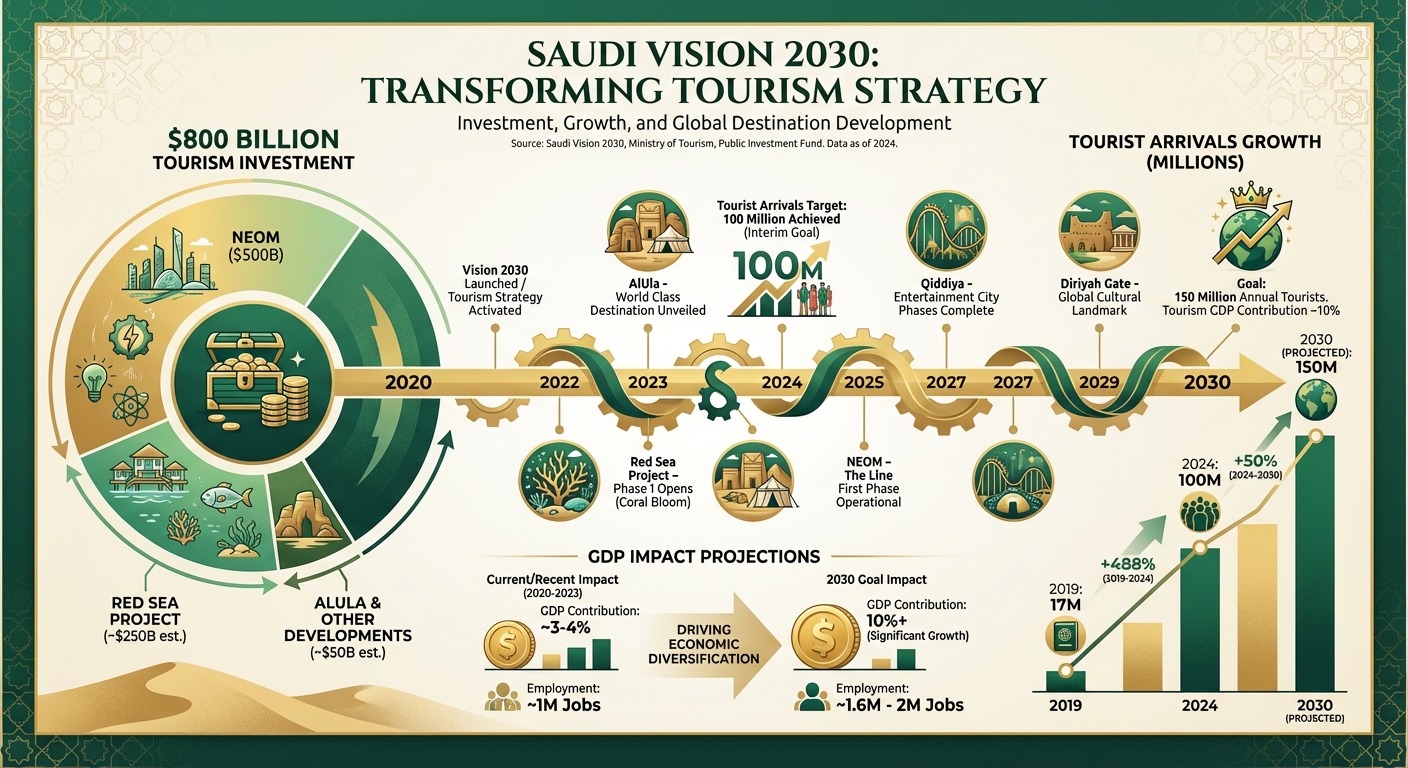

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the brainchild of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, is betting the kingdom’s future on tourism. The scope is almost absurd: NEOM, a $500 billion sci-fi mega-city being built from scratch in the desert. The Red Sea Project, luxury resort islands targeting ultra-wealthy travelers. AlUla, an ancient archaeological site being developed into Saudi Arabia’s answer to Petra.

This isn’t gradual organic growth. It’s forced evolution powered by massive capital deployment. The goal is 150 million annual tourists by 2030, generating 10% of the country’s GDP. For context, that would make tourism as important to Saudi Arabia’s economy as oil exports currently are. It’s an economic moon shot.

The projects themselves are genuinely impressive. Massive construction, world-class facilities, and infrastructure that rivals anything in Dubai or Singapore. The kingdom is spending its oil wealth to build the post-oil economy before oil becomes obsolete. It’s a race against time, and so far, the numbers suggest it might actually work.

The Cultural Contradiction

Here’s the problem: Saudi Arabia has a serious image problem in the West. The country is known for strict interpretations of Islamic law, restrictions on women’s rights, the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and involvement in the Yemen conflict. These aren’t small PR challenges. They’re fundamental moral concerns for many Western travelers.

To overcome this, the government is creating what amounts to two Saudi Arabias. In designated “tourist zones,” the rules are relaxed. Women can dress differently. Unmarried couples can share hotel rooms. Alcohol restrictions are loosened. It’s a kind of cultural segregation, areas where foreign money is welcome and foreign customs tolerated, separated from the rest of the country where traditional norms remain enforced.

This approach allows the kingdom to welcome Western money without fully liberalizing society. Whether it’s sustainable long-term is an open question. Eventually, the contradictions between tourist zones and the broader society might become impossible to maintain. Or the exposure to foreign culture might gradually shift Saudi society itself. No one knows which outcome is more likely.

The Economic Necessity

Why the urgency? Oil dependence is a ticking time bomb. As AI companies race to secure nuclear and other power sources to fuel their data centers, global efforts to transition to renewable energy mean peak oil demand could arrive within 10 to 20 years. When that happens, economies built entirely on oil exports face collapse. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other Gulf states saw this coming and are desperate to diversify before it’s too late.

Youth unemployment across the region is chronically high, with 60-70% of the population under 35 and not enough jobs to go around, a stark contrast to Japan’s aging population crisis but with its own set of pressures. Tourism offers a way to create millions of service sector jobs: hotels, restaurants, tour guides, entertainment, retail. It’s a strategy to stabilize the economy against volatile oil prices and demographic pressure.

It’s also a soft power play. Countries that host millions of tourists gain cultural influence and economic leverage. The UAE already proved this model works. Now Saudi Arabia and others are trying to replicate it at massive scale.

What Travelers Actually Experience

Western tourists who’ve visited report being surprised, often pleasantly. The landscapes are genuinely stunning, from desert dunes to Red Sea coastlines to ancient archaeological wonders, offering an alternative to overtourism hotspots and the kind of authentic experience that Bhutan pioneered with its sustainable tourism model. Hospitality is warm and welcoming. Infrastructure is often world-class, sometimes exceeding what you’d find in Europe or North America.

But the experience comes with trade-offs. Cultural adjustments regarding dress codes and behavior, even in tourist zones. High costs, especially for luxury destinations marketed to wealthy travelers. And the political discomfort of supporting regimes with documented human rights issues. Many travelers struggle with the ethical calculus: can you appreciate the beauty and culture while disagreeing with the government?

The Bottom Line

The Middle East’s tourism revolution is real. The investments are massive, the infrastructure is impressive, and tourists are coming in numbers that would’ve seemed impossible a decade ago. Whether this translates into long-term economic transformation depends on variables no one can predict: oil prices, geopolitical stability, social change, and whether Western travelers can reconcile their ethical concerns with their desire to explore new places.

For now, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Oman are proving that with enough money and political will, you can transform your economy faster than anyone thought possible. The harder question is whether the transformation will outlast the oil money funding it.

This analysis draws on Saudi Arabian tourism statistics, Vision 2030 project documentation, Jordan and Oman tourism data, economic assessments of tourism investments, traveler surveys, and regional policy analysis.

Sources: Saudi Vision 2030 documentation, regional tourism statistics, economic analysis.