Most countries are still debating whether they’ll meet their climate commitments. Bhutan skipped that conversation entirely. The tiny Himalayan kingdom doesn’t just offset its carbon emissions, it absorbs more than twice what it produces. While the world emits 36 billion tons of CO2 annually, Bhutan is running a carbon surplus, pulling 6 million tons from the atmosphere each year while emitting only 3 million.

This isn’t creative accounting or carbon credit shuffling. It’s written into the constitution. Article 5, Section 3 legally mandates that 60% of Bhutan’s territory must remain forested forever. Not as a policy goal or a political promise, but as an unchangeable constitutional requirement. Currently, 72% of the country is covered in forests, and it’s staying that way. While nations race to exploit the Arctic’s resources, Bhutan shows there’s another way.

In a world where environmental protection is usually the first thing sacrificed for economic growth, Bhutan proves the opposite is possible. The question is whether anyone else is willing to follow the blueprint.

The Constitutional Commitment

Bhutan’s environmental policy isn’t a politician’s campaign promise that evaporates after the next election. It’s baked into the founding document of the state, immune to political whims or economic pressure. When the country transitioned from absolute monarchy to constitutional democracy in 2008, protecting the environment wasn’t a nice-to-have, it was non-negotiable.

The result is a country that functions as a net carbon sink for the planet. Those forests absorb CO2, regulate water systems, prevent soil erosion, and provide habitat for endangered species including snow leopards, red pandas, and Bengal tigers. Bhutan has become one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots, all while maintaining a functional modern economy.

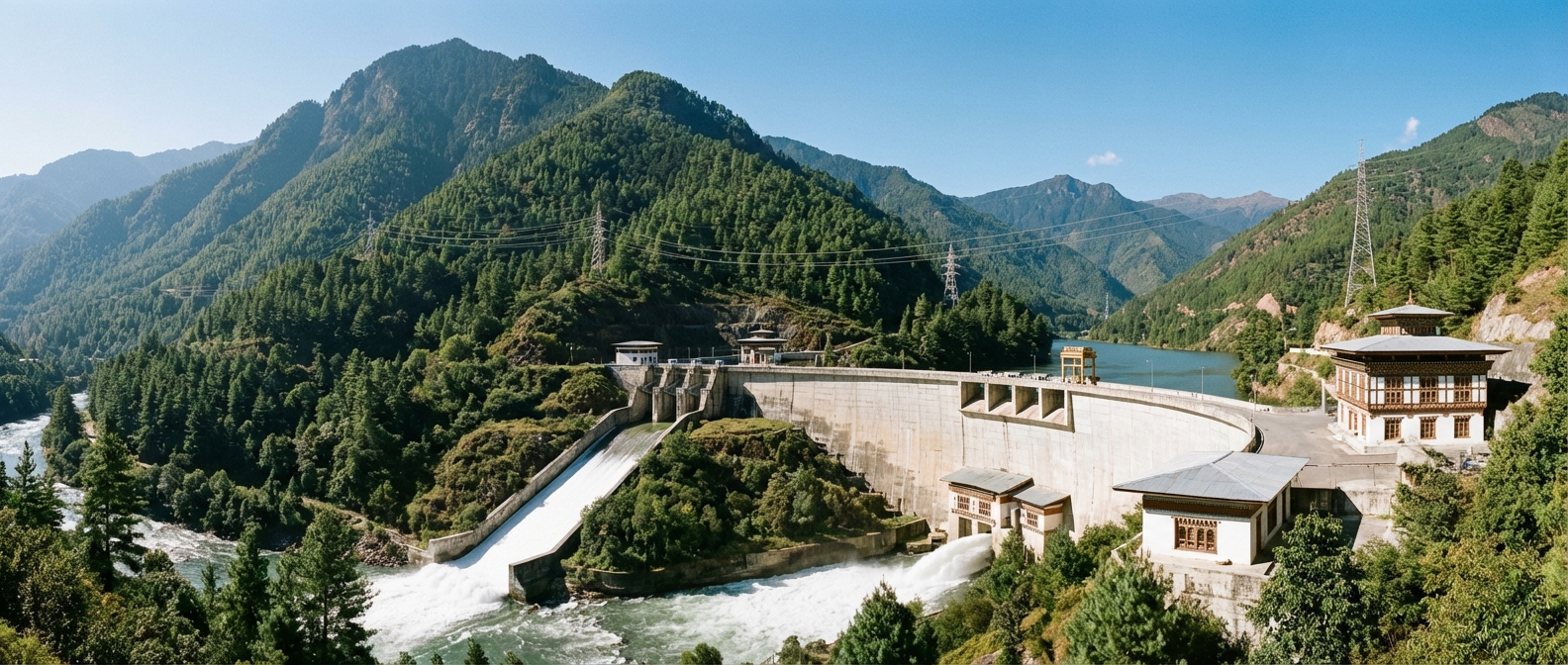

The country’s energy system is entirely hydropower, fed by glacial melt from the Himalayas. Not only does this keep Bhutan’s grid 100% renewable, but the surplus electricity is exported to India, helping its massive neighbor reduce dependence on coal. The revenue from those exports, over $400 million annually, funds schools, hospitals, and infrastructure. It’s a virtuous cycle: environmental protection generates economic benefits, which fund more environmental protection.

Gross National Happiness Over GDP

The philosophical foundation of Bhutan’s model is “Gross National Happiness,” a development framework that measures progress across nine domains: psychological well-being, health, education, time use, cultural diversity, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity, and living standards. Notice that GDP is just one component, not the only metric.

This approach fundamentally changes the policy calculus. When a logging company proposes clearing forest for timber, the question isn’t “how much GDP will this generate?” It’s “does this improve overall happiness and ecological health?” Usually, the answer is no, and the proposal dies.

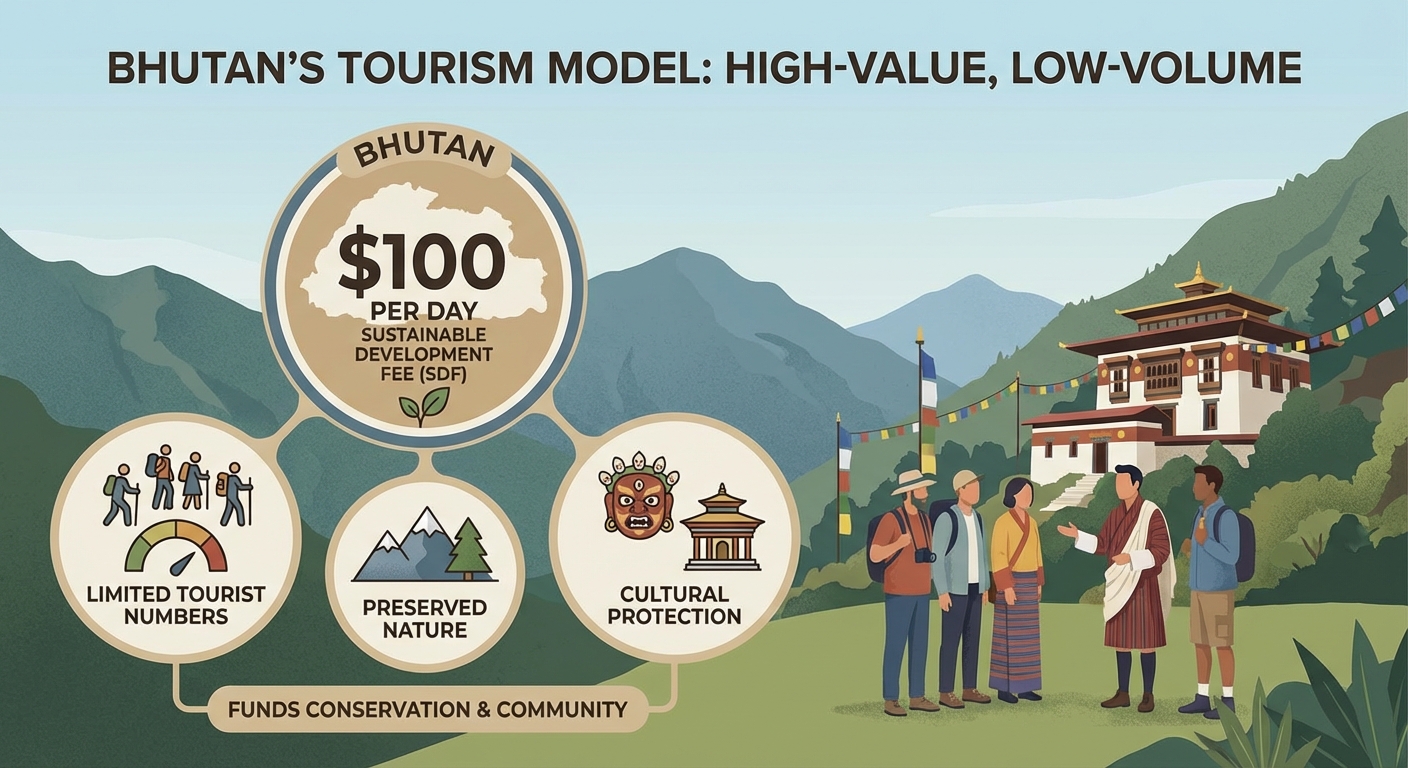

Tourism operates under the same logic. Instead of chasing mass tourism like Thailand or Bali, Bhutan charges a mandatory Sustainable Development Fee of $100 per visitor per day. This “high value, low volume” model keeps tourist numbers manageable, around 300,000 annually, preventing the overcrowding and environmental degradation that plague other destinations. The revenue, meanwhile, funds conservation and social programs.

Critics point out that Bhutan isn’t perfect. Youth unemployment hovers around 20%, many young people leave for opportunities abroad, and the economy remains heavily dependent on India. Climate change is a direct threat, with glacial melt disrupting water supplies and increasing flood risks. The country is small, landlocked, and lacks the natural resources or population to ever become an economic powerhouse.

The Bottom Line

Bhutan proves that environmental protection and economic development don’t have to be enemies. The country isn’t wealthy by GDP standards, but it’s stable, improving quality of life, and protecting its natural heritage for future generations. The key insight is constitutional protection: making environmental preservation legally untouchable, immune to short-term political or economic pressure.

Can this model scale? Probably not directly. Bhutan has unique geographic advantages, abundant water resources, a small population, and a relatively homogenous culture. But the core principle, prioritizing long-term ecological health over short-term extraction, is universal. In a world where demographic decline is reshaping national strategies, Bhutan’s focus on quality over quantity may prove prescient. In a world racing toward climate catastrophe, Bhutan is the country that decided not to race at all. And it’s winning.

Sources: Bhutan government reports, Royal Government GNH Centre, UN Development Programme, carbon accounting audits.