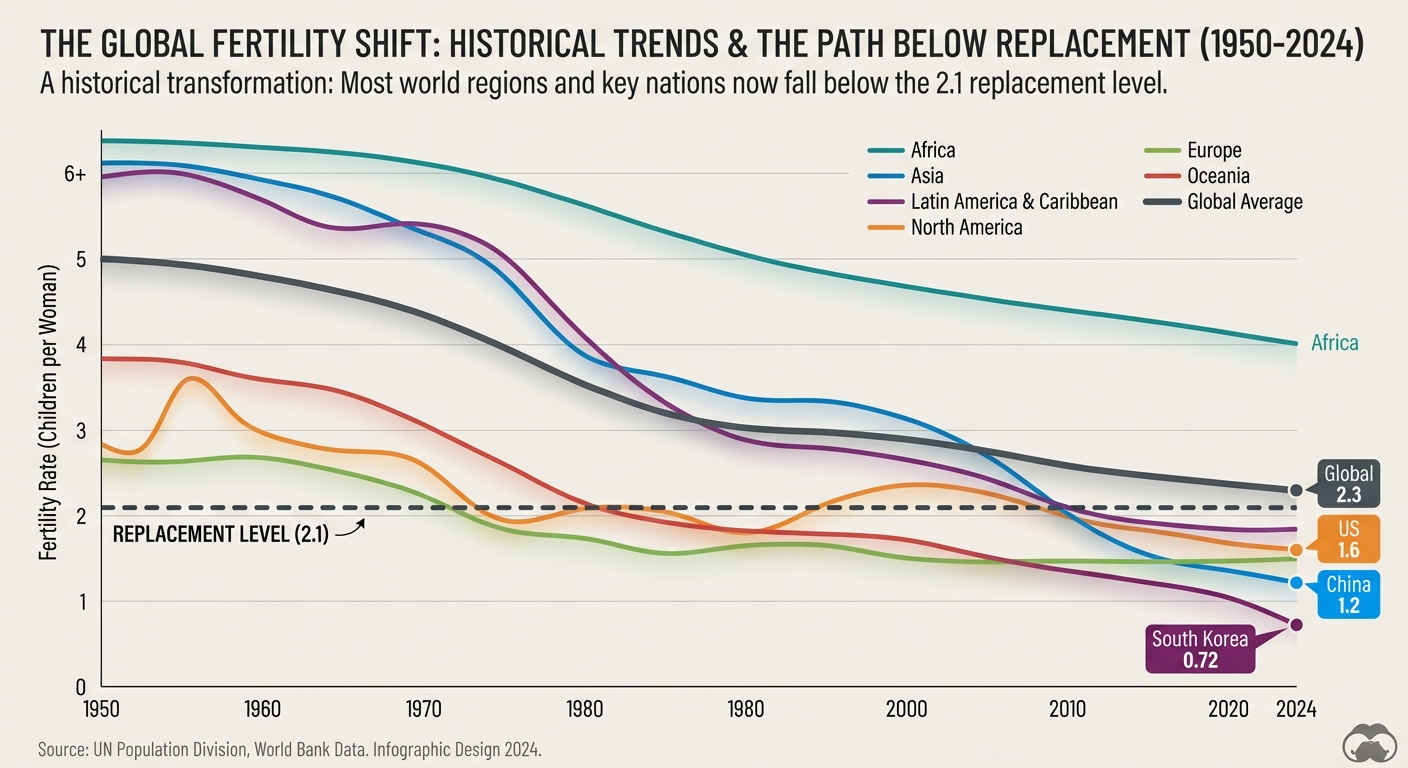

In 2024, a demographic milestone passed almost unnoticed: for the first time in human history, more than half the world’s population lived in countries with fertility rates below 2.1 children per woman. That’s the “replacement level,” the rate needed to maintain a stable population over time. Drop below it, and eventually, you start shrinking.

This isn’t just happening in wealthy Western countries anymore. Nearly all of Europe, East Asia, and North America are below replacement. But increasingly, so are Latin America, the Middle East, and parts of Southeast Asia. Global fertility has dropped to 2.3, down from 5.0 in 1950. South Korea holds the unwanted record at 0.72 births per woman, but the trend is universal.

By mid-century, the global population will likely peak and then begin to decline for the first time since the Black Death in the 1300s. This isn’t a prediction, it’s demographic momentum already locked in. And it’s going to reshape everything: economies, politics, culture, and the very structure of human civilization.

Why This Is Happening Everywhere

The drivers of declining fertility are structural and cultural, and they’re converging globally. Economic pressure is the biggest factor. Housing, education, and healthcare costs have exploded while wages stagnated. In wealthy nations, achieving financial stability now often takes until your 30s, shortening the biological window for having children. In poorer nations, aspirations are rising faster than incomes, creating the same squeeze.

Urbanization is another massive force. As humanity moves to cities, and 70% of us will be urban by 2050, the economics of children flip. On a farm, kids are labor assets who contribute to household income. In a cramped city apartment, they’re economic liabilities who consume resources for decades before contributing anything. The shift from rural to urban life is also a shift from seeing children as economic necessities to seeing them as lifestyle choices.

Women’s empowerment, while unequivocally positive, naturally correlates with lower birth rates. As women gain access to education and careers, many choose professional achievement and autonomy over large families. This is a rational response to societies that often fail to support working mothers, forcing women to choose between career and family rather than enabling both.

Cultural shifts matter too. Marriage rates are declining globally. Expectations for parenting have intensified, with enormous pressure and costs around education and child development. Many young people look at the financial and social costs of raising children and simply opt out.

The Economic Shockwave Coming

Our entire economic system is built on an assumption of perpetual growth: more workers, more consumers, more taxpayers. Population decline breaks this model in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Pensions and social safety nets are the most immediate crisis. Systems like Social Security were designed when there were four workers for every retiree. As that ratio drops to two-to-one or lower, the math simply fails. Governments face impossible choices: cut benefits for the elderly, raise taxes on a shrinking workforce, or print money and risk inflation. All options are politically toxic.

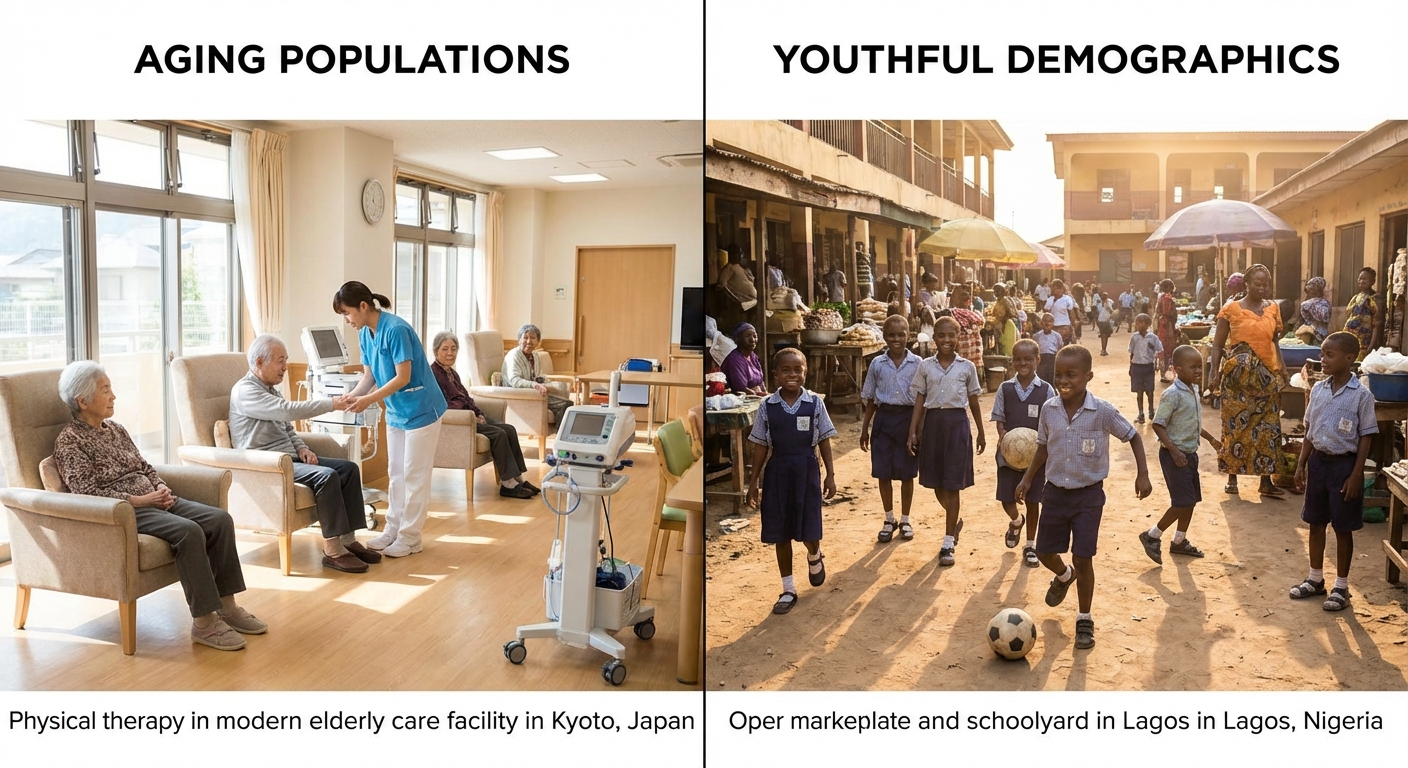

Labor shortages will become chronic across industries. This will drive wages up, which sounds good until you realize it also drives costs up, potentially creating stagflation. Housing markets that depend on growing demand to maintain values could face long-term stagnation or collapse in depopulating regions. Japan and Italy already have thousands of abandoned homes in rural areas, literal ghost towns where more people die than are born. Japan is actively trying to reverse this trend, with mixed results.

Innovation could slow as the average age increases and risk-taking younger populations shrink. Debt-to-GDP ratios will worsen as smaller workforces support larger retiree populations. The implications cascade through every sector of the economy.

The Geopolitical Earthquake

Demographics are destiny in geopolitics. China’s working-age population is already shrinking, undermining the economic engine that powered its rise. Europe’s population is projected to fall to just 7% of the global total by 2050, down from 25% a century ago, ending any pretense of the continent’s centrality to world affairs.

Meanwhile, India just became the world’s most populous nation with a much younger demographic profile, positioning it as a rising power. And Africa is booming. By mid-century, one in four humans will be African. Nigeria alone could have 400 million people. This will inevitably shift the center of global power and attention toward the Global South and away from the aging, shrinking populations of the West and East Asia.

Countries that adapt through automation, immigration, or radical policy innovation will survive this transition. Those that cling to old economic models will decline. It’s that simple. The competition for global resources will only intensify as population centers shift.

The Bottom Line

The age of endless population expansion is ending. We’re entering an era of contraction and demographic rebalancing. This will require reinventing our economic systems to function without growth, restructuring social safety nets for aging populations, and rethinking what national power means when your population is shrinking and graying.

Some countries will adapt successfully. Others will struggle and decline. But no one is exempt from this transition. It’s already happening, locked into the demographic data, and it will define the rest of the century. The countries having children today are shaping the global order of 2075. And most of the developed world isn’t among them.

This analysis draws on UN Population Division data, World Bank fertility statistics, demographic research from Pew Research and The Lancet, national statistics from multiple countries, and academic papers on fertility decline causes and economic consequences.

Sources: UN Population Division, World Bank, demographic research.