Everyone’s focused on the wrong resource war. While headlines obsess over semiconductors, oil, and artificial intelligence dominance, the real conflict of the 21st century is already underway. And it’s about something you can’t manufacture, substitute, or live without: water.

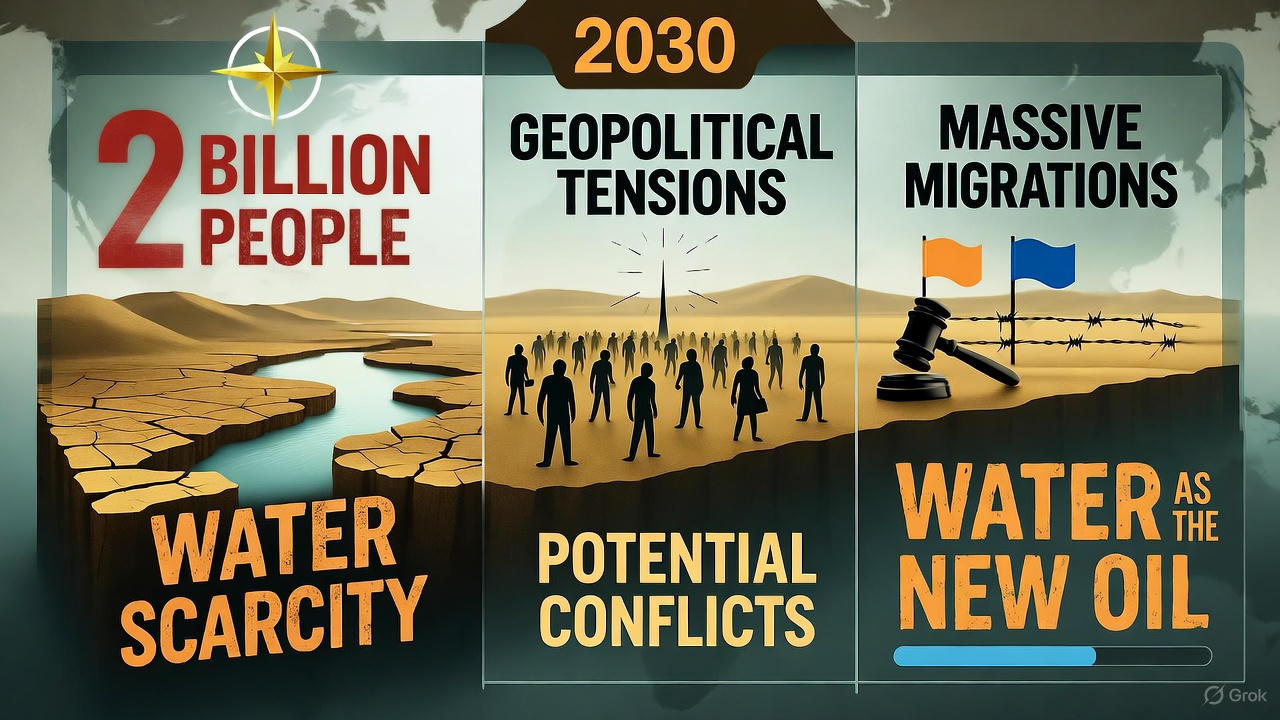

The United Nations estimates that by 2030, just five years from now, 2 billion people will face severe water scarcity. In some regions, that crisis isn’t coming, it’s here. Rivers that sustained civilizations for millennia are drying up. Reservoirs that watered millions are hitting record lows. And nations are quietly positioning themselves for conflicts that could make oil wars look quaint by comparison.

Unlike oil, you cannot invent an alternative to water. You cannot build a solar panel that replaces it, which is why nations are increasingly concerned about resource competition in previously inaccessible regions. Every person, every crop, every industrial process, every functioning society absolutely requires it. And as climate change shrinks supply while population growth increases demand, the competition is becoming zero-sum. When one country takes more, another gets less. And desperate countries do desperate things.

The Colorado River Crisis

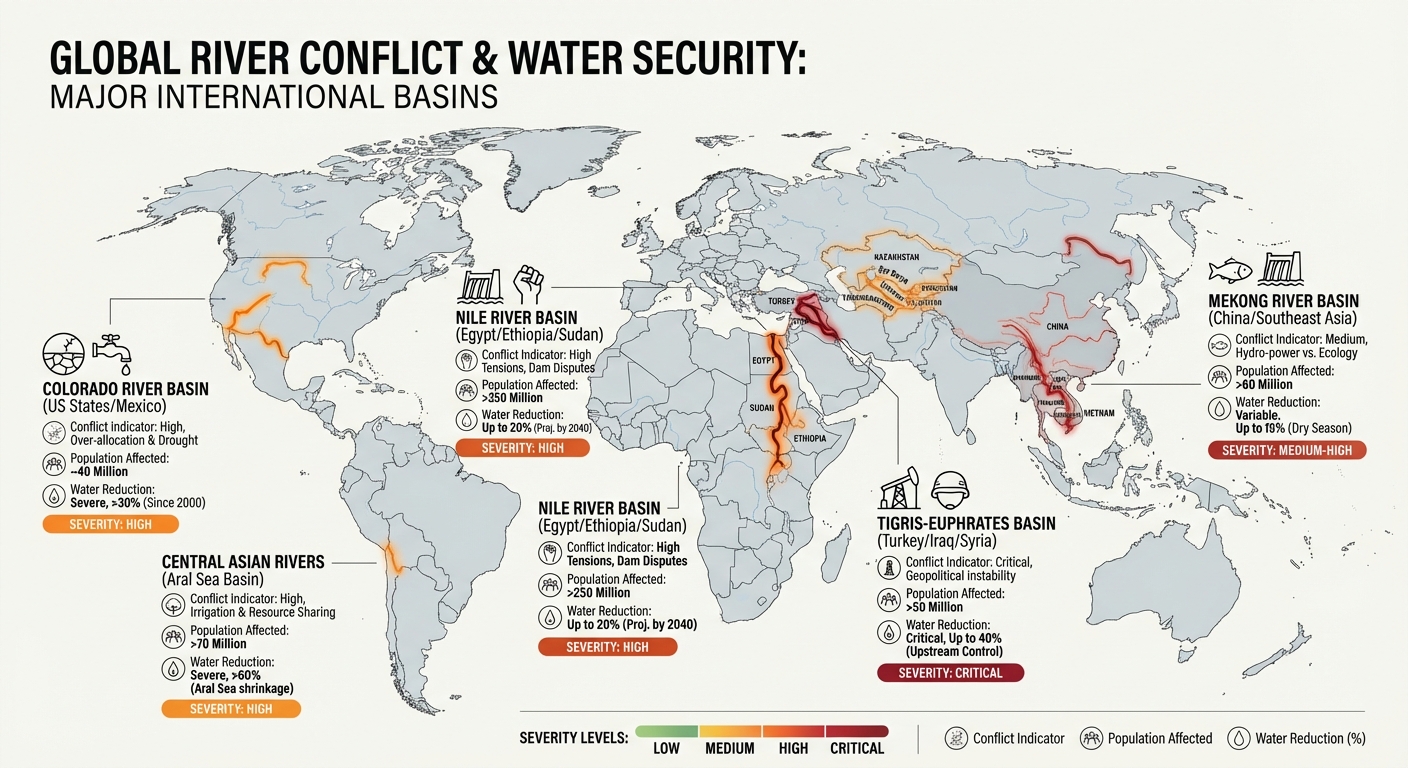

In the American West, the water reckoning has arrived. The Colorado River sustains 40 million people across seven states and irrigates 5.5 million acres of farmland that feeds much of the country. The river’s two main reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, have dropped to roughly 28% of capacity, leaving a stark white “bathtub ring” of mineral deposits 150 feet high on canyon walls, a visible scar of what’s been lost.

Seven states, California, Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico, are locked in an increasingly hostile standoff over dwindling flows. Each has legal claims dating back a century, when the river ran far higher than it does today. Those old agreements allocated more water than the river currently carries, creating a mathematical impossibility. Someone has to get less. No one wants it to be them.

The implications are existential for the region. Phoenix and Las Vegas, cities built in deserts on the assumption of infinite water, face genuine threats to long-term viability. The Imperial Valley in California, which produces massive quantities of America’s winter vegetables, could see farmland fallowed permanently. The federal government has brokered temporary cuts and emergency agreements, but the fundamental problem remains: the Southwest is using more water than the river can provide.

The hard choice, permanent, drastic reductions in consumption, remains politically toxic. Politicians would rather kick the can down the road than tell voters their lawns and pools are unsustainable. But the river doesn’t care about politics. The era of abundant water in the American West is over.

Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Fight Over the Nile

If water tensions in the U.S. are tense, the global flashpoints are approaching genuinely dangerous territory. In Northeast Africa, Ethiopia’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile has brought the region to the brink of conflict.

Egypt depends on the Nile for 90% of its freshwater. It’s not just important to Egypt, it’s existential. The country views any reduction in Nile flows as a direct threat to national survival. Ethiopia, meanwhile, sees the dam as a sovereign right and critical infrastructure for development, providing electricity to a population that desperately needs it. Sudan sits caught in the middle, geographically and politically.

Despite years of negotiations, no permanent agreement has been reached. Both countries have made thinly veiled threats. Egypt has suggested military action isn’t off the table. Ethiopia has filled the dam regardless of Egyptian objections. The situation remains a powder keg in one of the world’s most volatile regions.

China’s Weaponization of the Mekong

In Southeast Asia, the Mekong River sustains 60 million people across Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Or it did, until China effectively weaponized it.

China controls the Mekong’s headwaters and has built 11 major dams upstream, giving it complete control over the river’s flow. Downstream nations have suffered record low water levels, collapsed fish populations, and saltwater intrusion into the fertile Mekong Delta, Vietnam’s agricultural heartland. China can, and does, manipulate flows for its own economic benefit, giving it immense leverage over its southern neighbors.

Similar crises simmer across Central Asia, where post-Soviet republics fight over glacial meltwater, and in the Middle East, where Turkey’s dams on the Tigris and Euphrates reduce flows to Iraq and Syria, further destabilizing an already fragile region.

The Human Cost

Water scarcity is a primary driver of migration. When agriculture collapses, people move. Over 100,000 Guatemalans migrate to the U.S. annually, with prolonged drought as a major push factor. In 2022, Pakistan saw 20 million people displaced by catastrophic floods, a disaster worsened by poor water management infrastructure. The World Bank estimates that by 2050, water scarcity could displace up to 700 million people globally, adding to the global birth rate decline already reshaping demographics worldwide.

Wealthy nations are buying their way out. Israel, Singapore, and the UAE, which is pivoting its economy toward tourism and services, have invested billions in desalination and wastewater recycling, effectively engineering themselves out of scarcity. But these solutions are expensive and energy-intensive, accessible only to rich countries. The result is a deepening global water divide between those who can afford to solve the problem and those who can’t.

The Bottom Line

Water conflicts are different from other resource wars because they’re existential. You can survive without oil by switching to renewables. You can’t survive without water. International law on transboundary water resources is weak and largely unenforceable, leaving upstream nations with massive advantages and downstream nations with desperate choices.

As scarcity intensifies, expect more unilateral dam construction, more migration crises, rising food prices as agricultural regions fail, and genuine military conflicts over rivers. The wars of the 21st century might not be fought over ideology or oil, but over the ability to grow crops and drink. And unlike past resource conflicts, there’s no technological substitute waiting in the wings.

This analysis draws on data from UN Water, World Bank reports, the Pacific Institute, International Crisis Group assessments, and Stockholm International Water Institute research.

Sources: UN Water, World Bank, Pacific Institute, International Crisis Group, Stockholm International Water Institute.