For decades, sports science was based entirely on male physiology. Training programs, nutrition guidelines, and recovery protocols were designed for and tested on men, with female athletes told to follow the same regimens despite having fundamentally different hormonal environments. That’s changing. Emerging research reveals women should train differently across their menstrual cycles to optimize performance and recovery.

Estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone fluctuate dramatically across 28 days, affecting muscle strength, endurance capacity, fuel utilization, and injury risk. Female athletes who align training with their cycles report better performance and reduced injury compared to those who ignore these fluctuations. This isn’t about treating periods as weakness; it’s about leveraging biology for competitive edge.

Understanding the Hormone Cycle

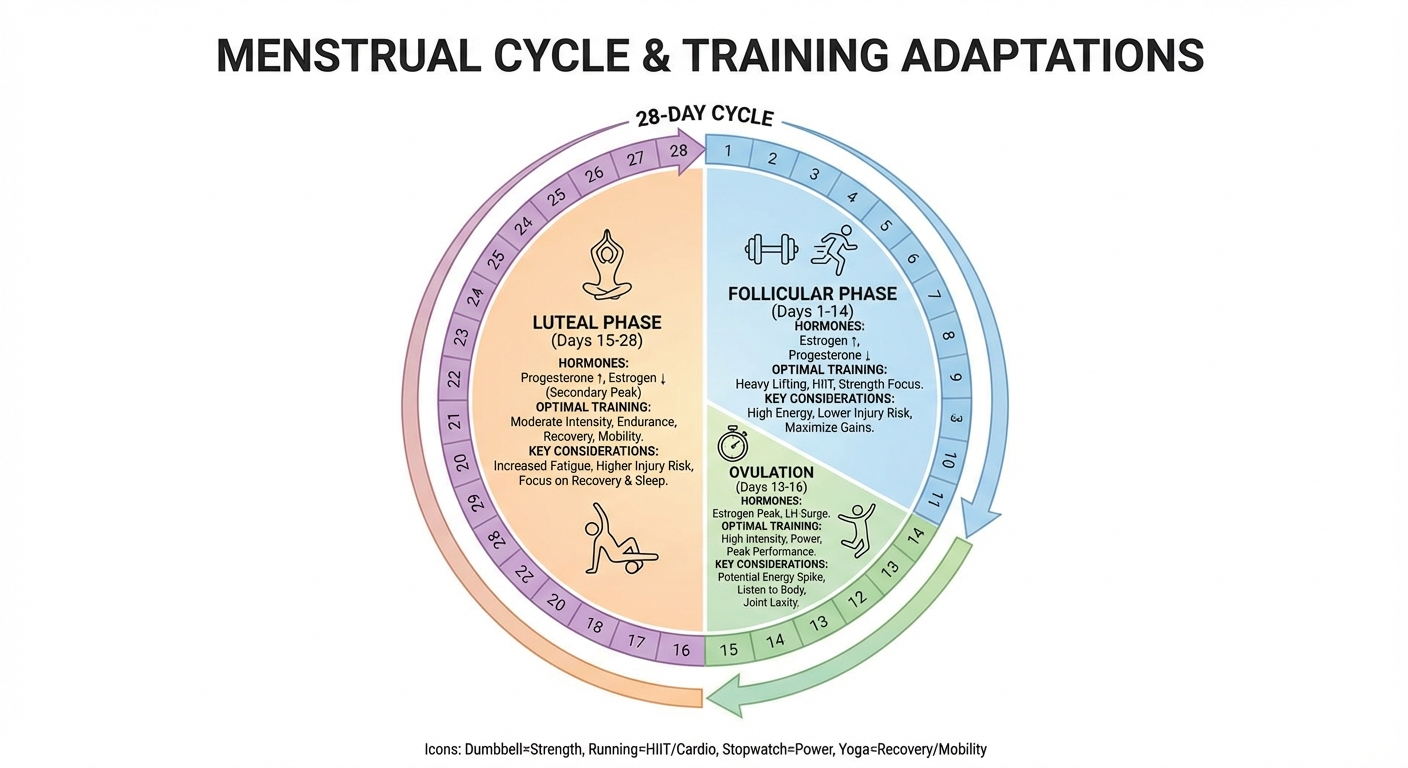

The menstrual cycle divides into distinct phases with different training implications. The follicular phase (days 1-14) is the power window. With rising estrogen and low progesterone, strength peaks, recovery is faster, and pain tolerance is higher. This is the time for heavy compound lifts, high-intensity intervals, and setting personal records.

The ovulation window (days 13-16) sees an estrogen spike, offering peak absolute strength but also peak injury risk due to increased ligament laxity. Training here should be high-intensity but cautious, with extended warm-ups and attention to form.

The luteal phase (days 15-28) is where things shift. As progesterone rises, recovery slows, body temperature increases, and high-intensity work feels harder. Training should pivot toward moderate intensity, higher volume with lower loads, and steady-state cardio. In the late luteal phase (PMS week), inflammation rises and energy drops, making this ideal for deload weeks, mobility work, and active recovery.

Elite Athletes Are Already Doing This

Professional athletes are increasingly adopting cycle-based training. British Olympic teams and national squads now track cycles to plan training peaks during the follicular phase and recovery during the luteal phase. Research backs this up, showing ACL tears cluster around ovulation and performance dips in the late luteal phase.

For recreational athletes, tracking is the first step. Using apps to note patterns in energy and performance allows better planning: scheduling max efforts in the first half of the cycle and being forgiving during the high-gravity days of late luteal phase. The goal isn’t to avoid training during certain phases, but to adjust intensity and expectations.

Nutrition Matters Too

Nutritional needs shift across the cycle. Higher carbohydrate intake is often needed in the luteal phase due to reduced insulin sensitivity. Increased protein helps counteract progesterone’s catabolic effects on muscle. Some athletes find they need 200-300 more calories per day in the luteal phase to maintain energy and recovery.

The Birth Control Factor

Hormonal birth control complicates this picture by flattening natural fluctuations. For women on the pill, cycle phases are artificial, meaning the natural performance peaks of the follicular phase and recovery drag of the luteal phase may be blunted. Some athletes time coming off birth control to align with competition seasons, while others prefer the consistency it provides. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer.

The Bottom Line

Female athletes have been training like men for decades, leaving performance on the table. Cycle-based training acknowledges that biology impacts athletic capacity, but it’s not a limitation, it’s a strategy. By pushing hard when the body is primed and recovering when it’s vulnerable, women can train smarter, not just harder. The science is clear: understanding your cycle isn’t just good health practice, it’s a competitive advantage.

For more on the evolution of women’s sports, read about the women’s sports breakthrough and the NBA’s European player development systems.

Sources: Sports science journals, female athlete research, British Olympic team data.