The United Nations was designed for a world with 50 countries. Today there are 193. The Security Council, the organization’s most powerful body, has five permanent members with veto power: the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom. All victors of World War II. All white-majority nations except China. All granted their seats in 1945.

That power structure made sense 80 years ago. It makes considerably less sense in 2025, as global demographic shifts reshape the balance of power, when those five countries can unilaterally block any action they dislike, no matter how much support it has from the rest of the world. Syria, Yemen, Ukraine, Gaza, dozens of conflicts where the UN stood paralyzed while people died, all because one or two permanent members said no.

After decades of mounting criticism and obvious dysfunction, the UN is finally attempting serious reform. Not cosmetic changes or committee reshuffles, but fundamental restructuring of who holds power and how decisions get made. Whether these reforms actually happen or die in endless diplomatic negotiations will determine whether the UN remains relevant for the next 80 years, or fades into ceremonial irrelevance.

The Structural Problem

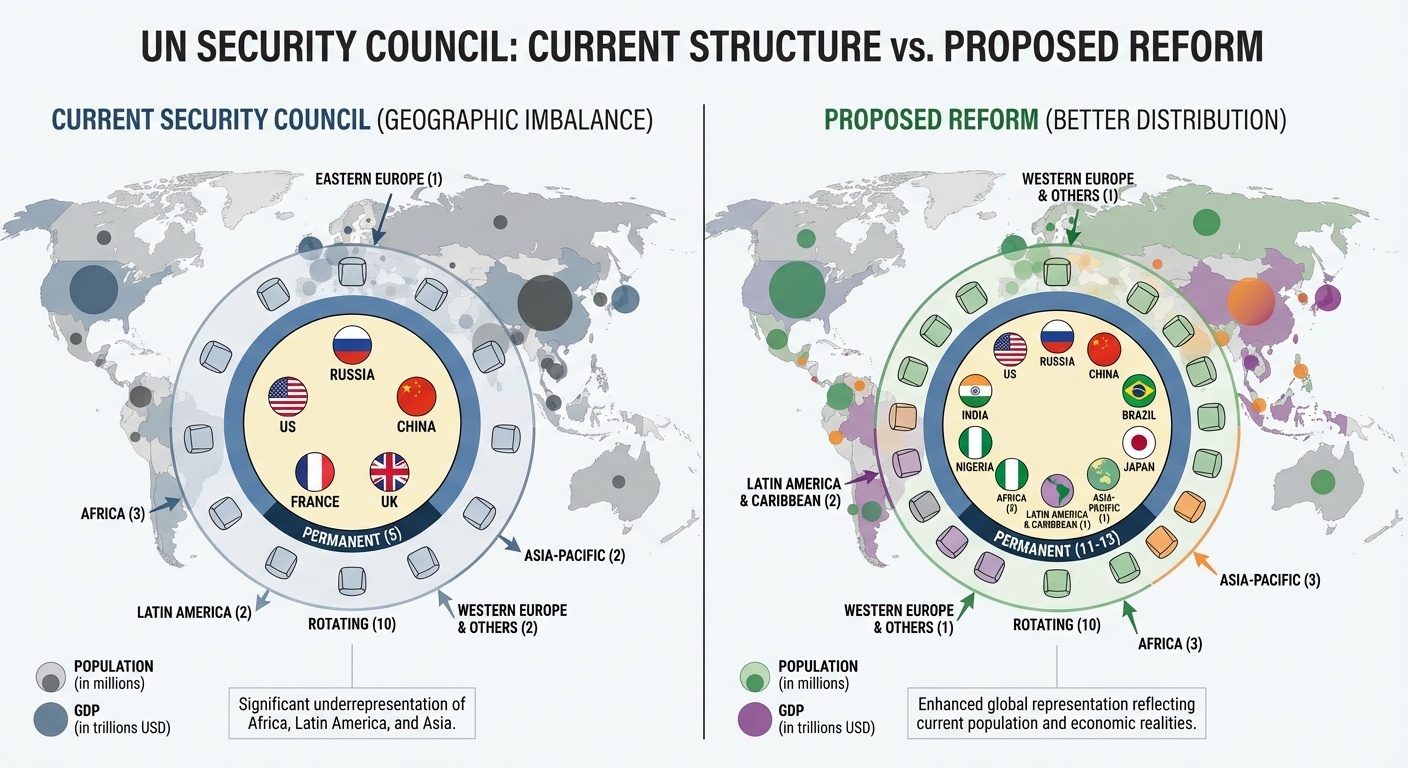

Even the UN’s strongest defenders admit the system is broken. The Security Council is fundamentally unrepresentative. Africa, home to 1.4 billion people, has no permanent seats. Latin America, 650 million people, no permanent seats. India, the world’s most populous nation and a top-five economy, no permanent seat. Meanwhile, France and the UK, former colonial powers with declining global influence, retain veto authority over world affairs.

The veto itself is the core dysfunction. A single country can block global consensus, rendering the institution impotent exactly when it’s needed most. Russia has vetoed resolutions on Syria 16 times, allowing Assad to wage war on his population without international intervention. The U.S. has vetoed dozens of resolutions on Israel and Palestine, regardless of evidence or international opinion. China blocks action on human rights. The pattern is consistent: permanent members protect their interests and allies, international law be damned.

Funding creates another distortion. The United States pays 22% of the UN budget, giving it outsized informal leverage beyond its formal veto. Meanwhile, the bureaucracy has grown bloated and slow-moving, often unable to respond to crises until it’s far too late.

The Reform Proposals on the Table

Several reform ideas have circulated for years, gaining renewed traction recently. The most ambitious is Security Council expansion, adding 6-8 new permanent members to better represent the modern world. Leading candidates include India, Brazil, Nigeria, Japan, and possibly Germany or an African Union rotating seat.

The logic is compelling: these nations represent massive populations, major economies, and geographic regions currently excluded from power. But expansion creates its own problems. More permanent members mean more potential vetoes, potentially making consensus even harder to achieve than it already is.

Another proposal targets the veto directly: eliminate it entirely, or at least limit it so a single country cannot block action alone. Perhaps require two vetoes, or allow a supermajority of the General Assembly to override. These ideas poll well in academic circles and among non-permanent members, but they’re dead on arrival with the current veto holders, none of whom will voluntarily reduce their own power.

More feasible proposals focus on adding permanent seats specifically for Africa and Latin America, addressing the colonial legacy of their exclusion. Another recent development is the creation of a Youth Advisory Council, giving younger generations a voice in UN proceedings, though it currently lacks formal decision-making power.

Why Reform Will Probably Fail

History suggests skepticism. Major reform efforts in the 1990s, 2005, and 2015 all collapsed. The fundamental problem is structural: the countries whose power would be reduced by reform must vote to approve that reduction. It’s asking turkeys to vote for Thanksgiving.

Why would Russia, facing international isolation, vote to dilute its veto? Why would France and the UK, clinging to post-imperial relevance, vote to share their seats? Why would the U.S., which benefits enormously from the current system, vote to empower rivals like India or Brazil?

Without an external enforcement mechanism, the incentives align perfectly with the status quo. Change requires unanimous agreement from the very people who benefit from not changing.

Increasingly, nations are simply bypassing the UN. The G20 handles major economic coordination. Regional organizations like the African Union, ASEAN, and the EU manage their own affairs. Ad hoc coalitions form to address specific crises. The UN is becoming a forum for speeches and symbolic resolutions, not actual problem-solving.

The Bottom Line

The UN faces a choice: reform or irrelevance. But reform requires the powerful to voluntarily cede power, something that almost never happens in human institutions. The most likely outcome is incremental change around the edges, more non-permanent seats, advisory councils, procedural updates, while the core power structure remains frozen in 1945.

Real reform probably requires a crisis severe enough to make the current dysfunction untenable. A major conflict the UN completely fails to prevent, a financial collapse, something that creates external pressure overwhelming enough to force change. Until then, the UN will continue to be exactly what it is: a useful forum for dialogue, a mechanism for coordinating humanitarian aid and development, and a paralyzed bystander when powerful nations decide to act badly.

The tragedy is that the world genuinely needs effective global governance. Climate change, pandemics, nuclear proliferation, and mass migration don’t respect borders. The intensifying competition over water resources alone demands coordination that current structures cannot provide. But the institution designed to handle these challenges is structurally incapable of doing so. And the people with the power to fix it have every incentive not to.

Analysis based on UN reform proposals, Security Council expansion debates, academic research on institutional effectiveness, historical documentation of previous reform attempts, veto usage patterns, and assessments of alternative global governance mechanisms.

Sources: UN reform proposals, Security Council records, international governance research.