To understand the sheer scale of what Meta just announced, consider this: the company’s new nuclear energy deals will generate more electricity than the entire state of New Hampshire consumes. We’re talking about 6.6 gigawatts of power capacity by 2035, all dedicated to feeding a single AI system called Prometheus.

On Thursday, Meta revealed it has signed agreements with three energy companies working on nuclear power technologies: Vistra, TerraPower, and Oklo. These aren’t pie-in-the-sky partnerships. They represent concrete commitments to build out the power infrastructure required to run what Meta is calling its most ambitious AI project ever, housed at a new supercluster computing facility in New Albany, Ohio.

The market noticed. Shares of Vistra jumped 10% on the news. Oklo climbed 8%. Meta itself closed 1% higher, a modest gain that belies the transformative nature of what the company is attempting. Here’s what’s actually happening and why it matters for the future of AI, energy, and the uncomfortable collision between the two.

The Power Problem No One Wants to Talk About

The dirty secret of the AI boom is that it runs on an absolutely staggering amount of electricity. Training large language models and running inference at scale requires power consumption that would have seemed absurd just five years ago. And as AI systems grow more capable, their energy appetite grows with them.

Meta’s Prometheus project represents the next generation of AI infrastructure, designed to support everything from the company’s AI assistant to its research into artificial general intelligence. But building a system that powerful means solving a problem that has quietly become one of the biggest bottlenecks in AI development: where does all the electricity come from?

The answer, increasingly, is nuclear. Meta joins Microsoft, Google, and Amazon in turning to nuclear power as the only realistic path to meeting AI’s energy demands at scale while maintaining any semblance of climate commitments. Unlike solar and wind, nuclear provides consistent baseload power regardless of weather conditions. Unlike natural gas, it doesn’t produce direct carbon emissions during operation.

The broader trend of tech giants embracing nuclear has been building for over a year now. But Meta’s announcement stands out for its sheer ambition. At 6.6 gigawatts, we’re talking about roughly the output of six large nuclear reactors, all dedicated to a single company’s AI operations.

Who Meta Is Partnering With

The three companies Meta has chosen represent different approaches to next-generation nuclear power, suggesting the company is hedging its bets rather than committing to a single technology.

Vistra is the most conventional partner. The company operates one of the largest fleets of power plants in the United States, including nuclear facilities. Their involvement likely means extending the lifespan of existing nuclear plants and potentially building new capacity using proven reactor designs.

TerraPower is where things get more interesting. Founded by Bill Gates in 2008, TerraPower is developing advanced reactor designs that promise to be safer, more efficient, and more flexible than traditional nuclear plants. Their Natrium reactor uses liquid sodium as a coolant instead of water, allowing for higher operating temperatures and potentially lower costs. TerraPower broke ground on its first commercial reactor in Wyoming in 2024.

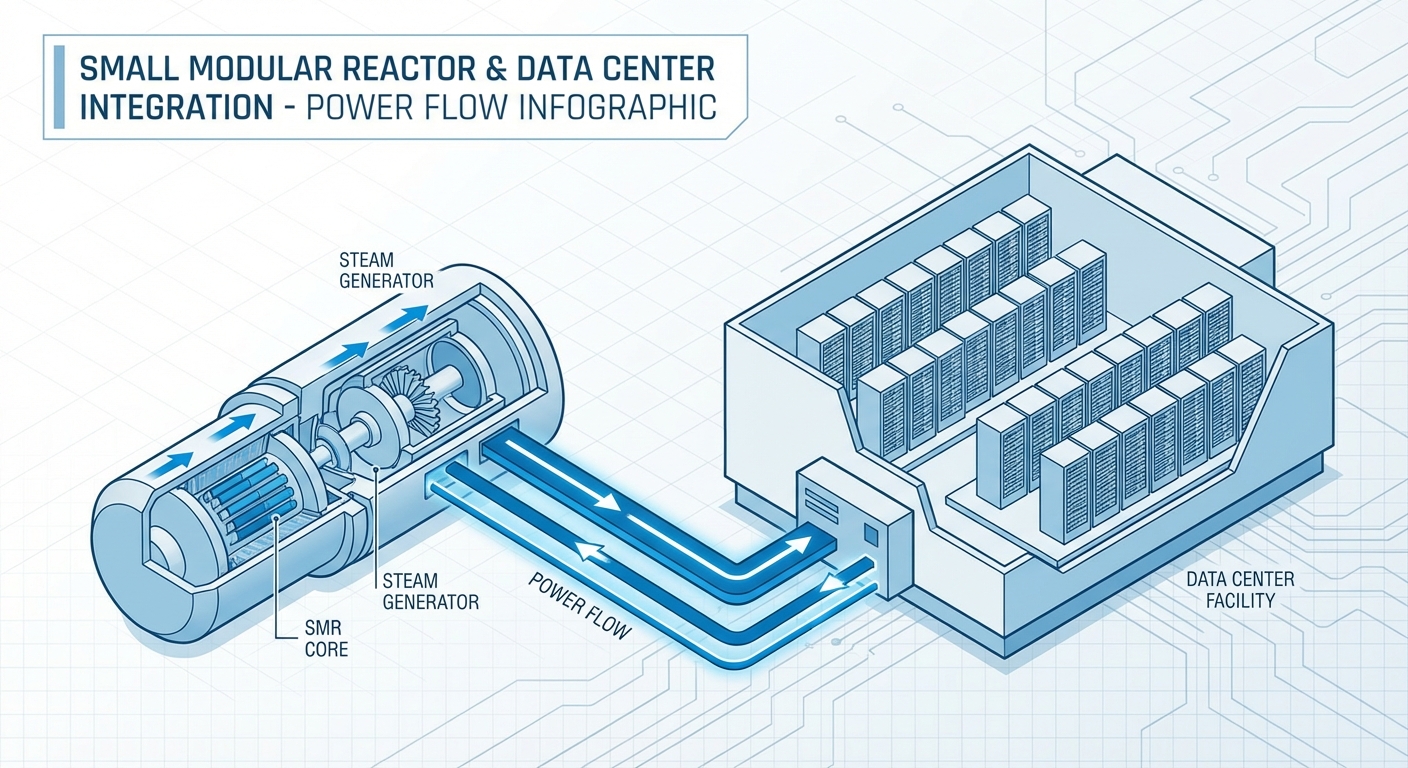

Oklo represents the most experimental approach. The company is developing small modular reactors (SMRs) that can be deployed more quickly and cheaply than traditional nuclear plants. SMRs have been the subject of intense interest from tech companies because they can be built closer to data centers, reducing transmission losses and grid dependency.

By partnering with all three, Meta is essentially betting on multiple horses in the race to scale nuclear power for AI. If traditional reactors prove most economical, Vistra can deliver. If advanced designs like TerraPower’s pan out, Meta has access. If SMRs become the preferred solution for tech campuses, Oklo is in the mix.

The Prometheus Supercluster

At the center of all this energy infrastructure is Prometheus, Meta’s next-generation AI computing system being built in New Albany, Ohio. While Meta has been characteristically vague about Prometheus’s specific capabilities, the scale of the power infrastructure tells its own story.

For context, Meta’s current largest AI training clusters consume roughly 150 megawatts of power. If the company is planning for 6.6 gigawatts of nuclear capacity by 2035, that suggests Prometheus could eventually operate at 40 times the scale of anything Meta runs today. Even accounting for growth in other operations and efficiency improvements, we’re looking at an AI system of unprecedented size.

The recent acquisition of Manus AI for $2 billion now makes more sense in this context. Meta isn’t just building bigger AI models. It’s constructing an entirely new tier of AI infrastructure, one that requires rethinking everything from chip design to power generation.

Industry analysts have speculated that Prometheus is designed to train models that would dwarf anything currently in existence, potentially including systems designed to achieve artificial general intelligence. While Meta hasn’t confirmed this, the infrastructure investments certainly suggest ambitions beyond incremental improvements to existing AI products.

The Climate Calculation

Meta is framing these deals as part of its commitment to clean energy and carbon reduction. Nuclear power produces no direct carbon emissions during operation, making it attractive for companies facing pressure over the climate impact of AI development.

But the picture is more complicated than the press releases suggest. While nuclear is low-carbon during operation, the construction of new facilities and the mining and enrichment of uranium carry their own environmental footprints. And the 2035 timeline for 6.6 gigawatts of capacity means Meta will need to rely on other power sources, likely including natural gas, for years as the nuclear infrastructure comes online.

There’s also the question of nuclear’s own challenges. New reactor construction in the United States has a troubled recent history, with projects running billions over budget and years behind schedule. The advanced reactor designs Meta is betting on have yet to prove they can be built economically at scale. And despite safety improvements, public perception of nuclear power remains mixed following incidents like Fukushima.

Still, the alternatives are arguably worse. Running AI infrastructure on fossil fuels would make tech companies’ climate commitments meaningless. Relying solely on renewables would require massive battery storage systems that don’t yet exist at the necessary scale. Nuclear, for all its challenges, may simply be the least bad option for powering the AI future.

What This Means for the Industry

Meta’s announcement accelerates a transformation that’s been building throughout the tech industry. The companies building the most advanced AI systems have realized that power, not chips, may become the ultimate bottleneck. Securing energy supply is now as strategically important as securing semiconductor supply.

This creates interesting dynamics. Tech companies are essentially becoming energy companies, making multi-decade commitments to power infrastructure that will shape the industry long after current AI models are obsolete. The partnerships announced today will influence where data centers get built, which energy technologies succeed, and how much electricity is available for everyone else.

For regulators and policymakers, Meta’s announcement raises questions about whether it makes sense for private companies to be making decisions of this magnitude about energy infrastructure. The power Meta is contracting for could serve millions of homes. Instead, it will serve AI systems whose benefits to society remain subject to debate.

The Bottom Line

Meta just made one of the largest corporate commitments to nuclear power in history, and they did it to power a single AI system. Let that sink in.

The Prometheus supercluster and its 6.6 gigawatts of nuclear capacity represent a bet that AI development will continue to scale, that nuclear power can be built out fast enough to meet that demand, and that the benefits of advanced AI will justify the enormous infrastructure investments required.

Whether that bet pays off remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: the AI industry has outgrown the electrical grid as we know it, and companies like Meta are now in the business of building their own power infrastructure. The age of AI megastructures has begun.