Seven of China’s most prestigious universities are introducing a new undergraduate major that didn’t exist five years ago: “embodied intelligence.” The program combines robotics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence into a single discipline designed to produce engineers who can build machines that move, sense, and think.

Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Zhejiang University are leading the initiative, with five other elite institutions following. The timing isn’t coincidental. Chinese officials estimate the country needs an additional one million professionals in robotics-AI fields over the next decade, and current educational pathways aren’t producing them fast enough.

What “Embodied Intelligence” Actually Means

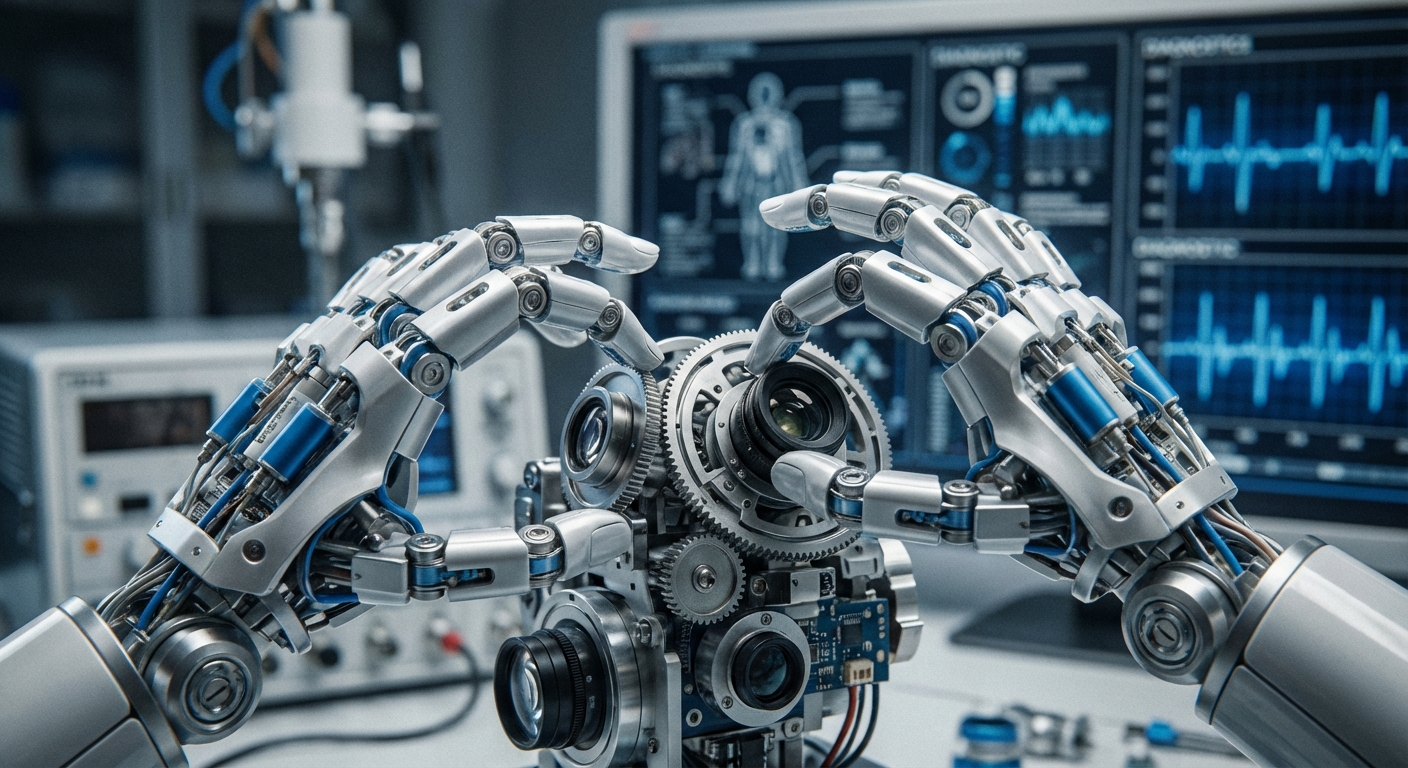

The term sounds like academic jargon, but the concept is straightforward. Traditional AI research focuses on software: algorithms that process information, generate text, or recognize patterns. Embodied intelligence means AI that exists in a physical form, robots that can interact with the real world, not just process data about it.

Think of the difference between ChatGPT and a robot that can walk into your kitchen and make breakfast. Both require AI, but the robot needs to understand physics, navigate three-dimensional space, manipulate objects with varying properties, and handle the messiness of reality rather than the cleanliness of digital inputs.

This is where robotics meets AI in ways that neither field has fully solved. A robot arm in a factory repeats precise movements thousands of times. A robot that can function in unstructured environments, homes, streets, construction sites, needs intelligence that adapts to unpredictable situations.

Why China Is Moving Aggressively

China’s bet on embodied intelligence connects to several national priorities. The country’s manufacturing sector faces rising labor costs and an aging workforce. Robots that can perform complex tasks could address both problems while keeping production domestic.

The geopolitical dimension is explicit. Chinese officials regularly cite the need for technological self-sufficiency, particularly in areas where Western countries might restrict access. Advanced robotics and AI represent strategic technologies that China doesn’t want to depend on imports to develop, much like its Arctic territorial claims are about securing future resources.

There’s also the competitive dynamic with the United States. American companies like Boston Dynamics, Tesla (with its Optimus robot), and various startups are pushing humanoid robotics forward. China sees this as a race it can’t afford to lose, and training a million specialists is how you win races that span decades.

The Curriculum Challenge

Creating a new academic discipline isn’t simple. Traditional university departments have established curricula, tenured faculty, and institutional inertia. Embodied intelligence requires expertise that spans mechanical engineering, computer science, electrical engineering, cognitive science, and even philosophy (for questions about machine consciousness and decision-making).

The Chinese universities are taking an interdisciplinary approach, drawing faculty from multiple departments and creating new courses that don’t fit traditional categories. Students will study control systems alongside deep learning, sensor physics alongside natural language processing.

What This Means for Global Competition

The talent pipeline matters enormously for long-term technological competition. Countries that graduate more engineers with relevant skills have more capacity to innovate, commercialize, and scale new technologies.

China already produces more engineering graduates than any other country, though quality varies significantly. By creating dedicated programs at elite universities, the country is trying to ensure a steady supply of top-tier talent specifically for embodied intelligence applications.

American universities have strong robotics and AI programs, but they’re not specifically designed around this integrated discipline. The ongoing AI transformation affecting every industry, from agentic AI systems to enterprise adoption, will increasingly require people who understand both the software and physical dimensions.

Whether dedicated undergraduate programs produce better results than traditional paths (major in computer science, specialize in robotics in graduate school) remains to be seen. China is betting that starting integration earlier produces engineers who think differently about the intersection of AI and physical systems.

The million-professional target is ambitious, perhaps unrealistically so. But the attempt signals how seriously China takes this domain, especially as Big Tech pours billions into India’s AI infrastructure. They’re not waiting to see if embodied intelligence becomes important. They’re assuming it will and training the workforce now.

Sources: South China Morning Post, Xinhua, Nature, Times Higher Education.