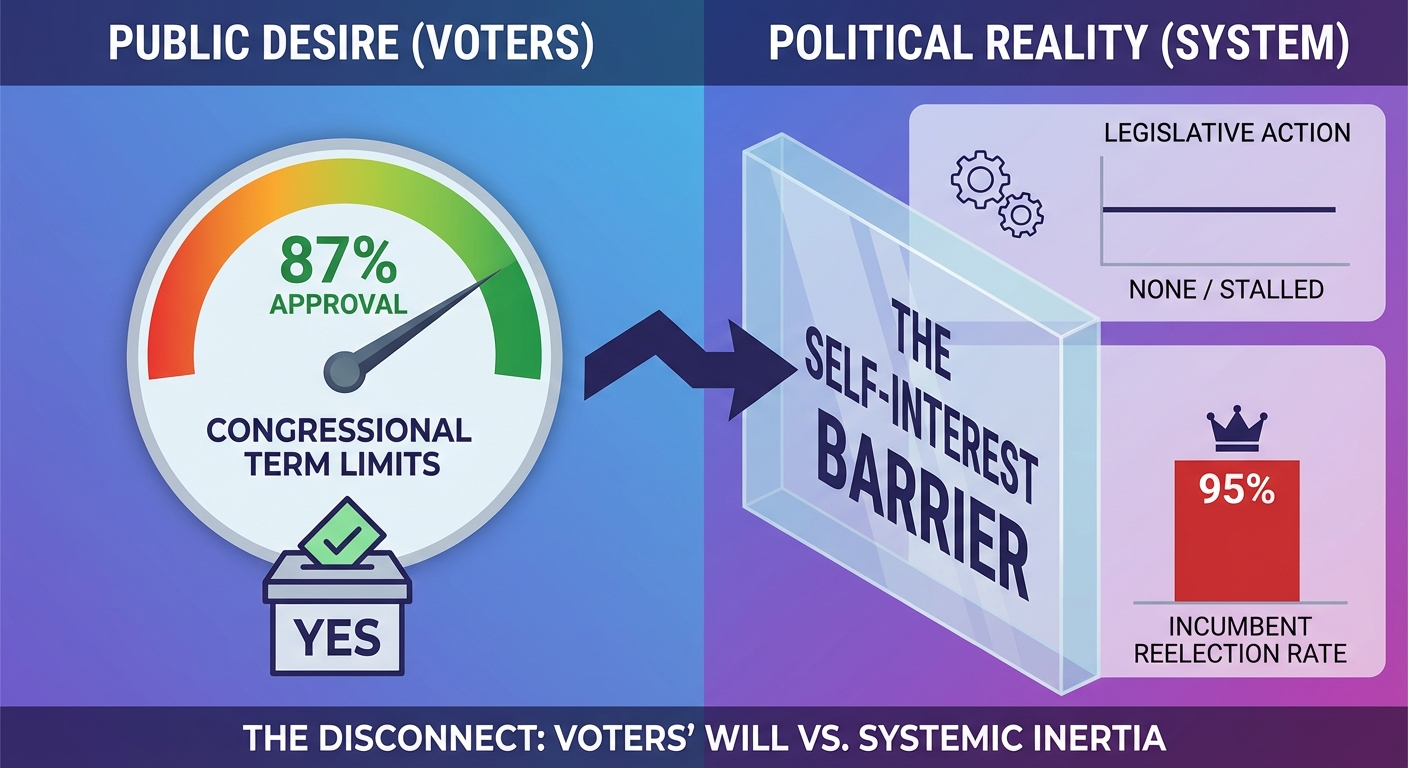

87% of Americans support congressional term limits. Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all agree, which basically never happens. Yet members of Congress can serve unlimited terms. Some have held office for 40+ years. The average senator has served over a decade.

Critics say this creates entrenched power, reduces accountability, and turns temporary public service into a permanent political class. Supporters argue experience and institutional knowledge matter. But the public has spoken: 87% want limits. That’s higher approval than any policy or politician gets. So why hasn’t it happened?

The Self-Interest Problem

The proposal is straightforward: 12-year limits for both House and Senate, mirroring the presidential limit. But passing a constitutional amendment requires two-thirds of Congress to vote for it. You’re asking them to vote themselves out of a job.

Incumbents benefit massively from the status quo. They build seniority, amass power, and virtually guarantee reelection. Incumbent reelection rates hover around 95%. Unless they’re already retiring, they have zero incentive to limit their careers. They argue term limits would empower lobbyists and unelected staff by removing experienced legislators, but the self-preservation motive is obvious.

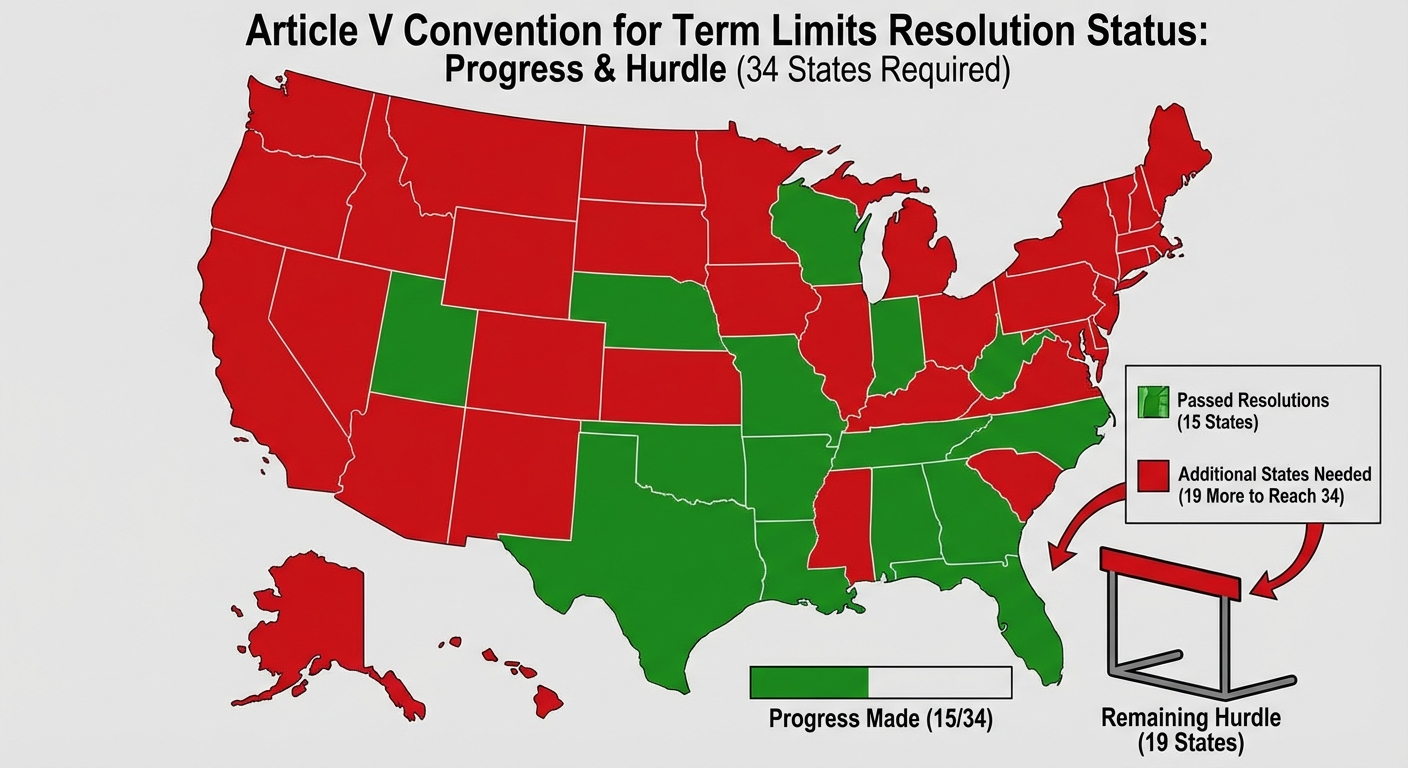

The State Convention Path

Since Congress won’t act, 15 states have passed resolutions calling for an Article V Convention to propose the amendment directly. If 34 states join, they can bypass Congress entirely. This “Convention of States” movement is the only realistic legal path forward, but it needs 19 more states.

State-level experiments with term limits offer mixed results. In states that implemented them for legislatures, turnover increased, but so did the power of lobbyists and executive branches. Inexperienced lawmakers often rely more on special interests to write complex bills. The data suggests term limits change the players but don’t necessarily fix the game.

The Debate

Proponents argue limits would break the incumbency advantage, reduce corruption, and bring fresh perspectives. It would force politicians to focus on governing rather than endless fundraising for career-long seats.

Opponents counter that it removes the most effective legislators, destroys institutional memory, and limits voter choice. Elections are term limits, they say. If voters want someone gone, they can vote them out. The counter-argument: gerrymandering and campaign finance laws make unseating incumbents nearly impossible.

The Bottom Line

Congressional term limits have overwhelming public support and essentially zero chance of passing through Congress. The state convention path is possible but likely decades away. The disconnect between voter preference and system delivery isn’t a bug, it’s a feature designed to protect existing power. Term limits remain the most popular policy that will probably never happen. For more on how voters are responding to political dysfunction, see the surge in independent voters. And for another example of direct democracy bypassing traditional channels, check out participatory budgeting.

Sources: Gallup polling data, Congressional Research Service, U.S. Term Limits organization, state legislative records.