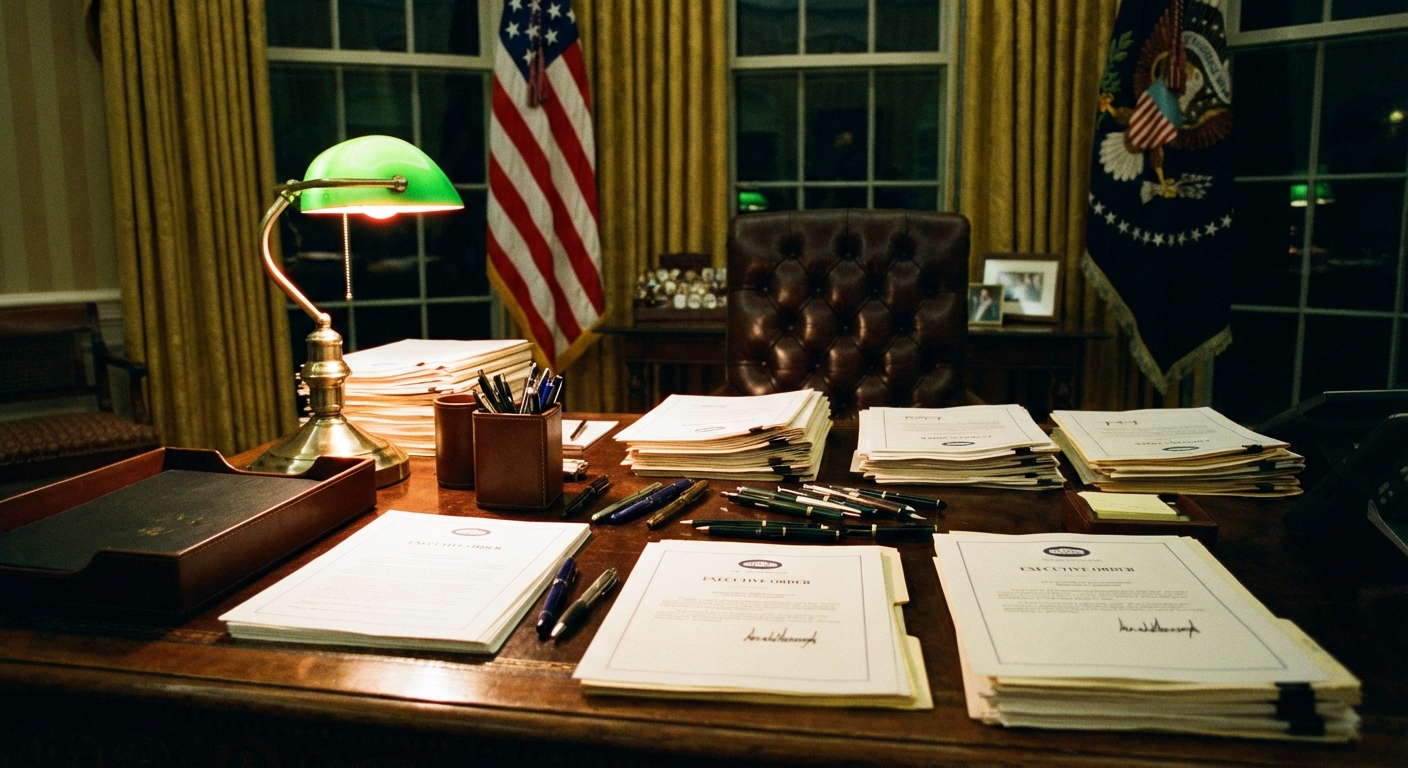

One year ago today, Donald Trump stood in the Capitol Rotunda and became the 47th President of the United States for the second time. Within hours, he signed 26 executive orders, 12 memorandums, and 4 proclamations, immediately beginning to reshape federal policy across virtually every domain. Twelve months later, the White House website lists 230 executive orders, 57 memoranda, and 121 proclamations, a pace of executive action that has no precedent in modern American history.

The volume alone tells a story about how Trump approaches the presidency differently than his predecessors. Where other presidents used executive orders sparingly, often for ceremonial purposes or narrow administrative changes, Trump has made them the primary mechanism for policy implementation. The approach reflects both impatience with the legislative process and a theory of presidential power that stretches constitutional boundaries in ways that continue generating legal challenges.

Whether this executive-order presidency has achieved its stated goals depends entirely on which goals you’re measuring. Immigration enforcement has intensified dramatically. Federal DEI programs have been eliminated. Climate regulations have been rolled back comprehensively. But many of the most ambitious orders face court challenges, and the underlying issues they address remain contested. The revolution Trump promised has arrived, but its permanence remains uncertain.

Day One and Its Consequences

The first executive order Trump signed before the crowd at Capital One Arena revoked approximately 80 actions from the Biden administration. This single stroke eliminated diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives across federal agencies, reversed climate policies, and rescinded immigration protections that had been built over four years. The speed was intentional: demonstrate from the first moment that the new administration would operate differently.

The birthright citizenship order, also signed on Day One, immediately generated the constitutional fight everyone anticipated. The 14th Amendment states that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens.” Trump’s order attempted to reinterpret “subject to the jurisdiction” to exclude children of undocumented immigrants. Federal courts blocked implementation within weeks, and the case is now headed to the Supreme Court.

The national emergency declaration at the southern border enabled military construction funding and expanded detention capacity without congressional appropriation. Arrests and deportations have increased significantly under this framework, though the underlying immigration system’s dysfunction remains unaddressed. Processing backlogs have actually grown as enforcement diverted resources from asylum adjudication.

DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency created by Day One order, has produced the most visible changes in federal operations. Led by Elon Musk during its initial months, the office identified billions in spending reductions, though critics note many “savings” involved freezing programs rather than eliminating genuine waste. The federal workforce has shrunk by approximately 8% through attrition and voluntary departures following the hiring freeze.

What Actually Changed

Immigration enforcement represents the clearest policy shift. Deportations have increased to levels not seen since the Obama administration’s peak enforcement years. The border wall has been extended, though completion of the full structure remains years away. Interior enforcement, including workplace raids and expanded cooperation with local police, has intensified in ways that affect communities far from the border.

Federal workforce composition has changed dramatically. DEI offices have been eliminated. Diversity training programs are gone. Hiring criteria that considered demographic factors have been replaced with what the administration calls “merit-based” standards. Civil rights groups argue these changes have reduced minority representation in federal employment, while administration officials claim they’ve improved hiring quality.

Environmental policy has reversed comprehensively. The Paris Climate Agreement withdrawal (Trump’s second) signaled the approach. Regulations on power plant emissions, vehicle fuel efficiency, and methane releases have been weakened or eliminated. Federal lands have been opened to additional drilling. The administration argues these changes reduce energy costs; environmentalists argue they accelerate climate damage that will cost far more in the long run.

Trade policy remains chaotic by design. Tariff threats have been announced, modified, withdrawn, and reimposed on various countries throughout the year. The unpredictability appears intentional, creating leverage for bilateral negotiations while generating constant uncertainty for businesses trying to plan supply chains. Whether the strategy produces better trade deals remains contested; it has certainly produced market volatility.

The Legal Challenges

Courts have blocked or limited approximately 40 executive actions over the past year. The birthright citizenship order faces the highest-profile challenge, but dozens of other orders have been enjoined on various grounds: exceeding statutory authority, violating constitutional provisions, or failing to follow required administrative procedures.

The administration’s response to court losses has varied. Some blocked orders have been revised and reissued with modifications addressing judicial concerns. Others remain in litigation while enforcement continues in jurisdictions not covered by injunctions. A few have been quietly abandoned when legal prospects seemed poor and political costs of losing outweighed benefits of fighting.

The Supreme Court will ultimately decide several of the most significant challenges. The birthright citizenship case arrives on a docket already shaped by the conservative majority Trump helped create during his first term. Court watchers expect most administration policies to survive, though the specific reasoning will determine how much latitude future presidents have to use executive orders for transformative policy changes.

Legal scholars debate whether the volume of executive action represents an appropriate use of presidential power or an unconstitutional end-run around Congress. The Constitution gives Congress the power to legislate, but it also gives presidents significant authority to execute laws and manage the executive branch. Where those boundaries lie has never been precisely defined, and Trump has pushed them further than any recent predecessor.

What Comes Next

The second year of Trump’s second term will likely see continued executive action, though potentially at a slower pace as the most immediately achievable changes have already been made. The administration has signaled interest in restructuring federal agencies more fundamentally, changes that may require legislation Congress seems unlikely to provide.

International relations will dominate attention as Greenland tensions, trade negotiations, and the Board of Peace initiative compete for presidential focus. Executive orders can shape how the administration pursues foreign policy, but they cannot compel other nations to comply with American preferences. The limits of unilateral action become clearer in international contexts.

Domestically, the 2026 midterm elections will shape what’s possible. Republican control of both chambers has facilitated confirmations and prevented oversight that might otherwise constrain executive action. Whether that continues depends on November’s results. Historical patterns suggest midterm losses for the president’s party, which could change the dynamic significantly.

The Bottom Line

One year of Trump 2.0 has produced more executive action than any comparable period in modern presidential history. Federal policy on immigration, diversity, environment, and trade has shifted dramatically through presidential directive rather than legislative process. Courts have blocked some changes while allowing others. The long-term durability of these transformations remains uncertain.

The approach reflects a theory of presidential power that prioritizes speed and unilateral action over consensus-building and institutional process. Supporters see a president finally willing to use the full authority of the office. Critics see an assault on constitutional design and democratic norms. Both perspectives capture something real about what the past year has demonstrated.

Whatever one thinks of the policy outcomes, the procedural transformation is significant. Trump has shown that a president determined to act unilaterally can accomplish substantial policy change without Congress. Whether that’s a feature or a bug of American government will be debated long after the specific policies have been modified, reversed, or normalized. The precedents being set may matter more than any individual executive order.