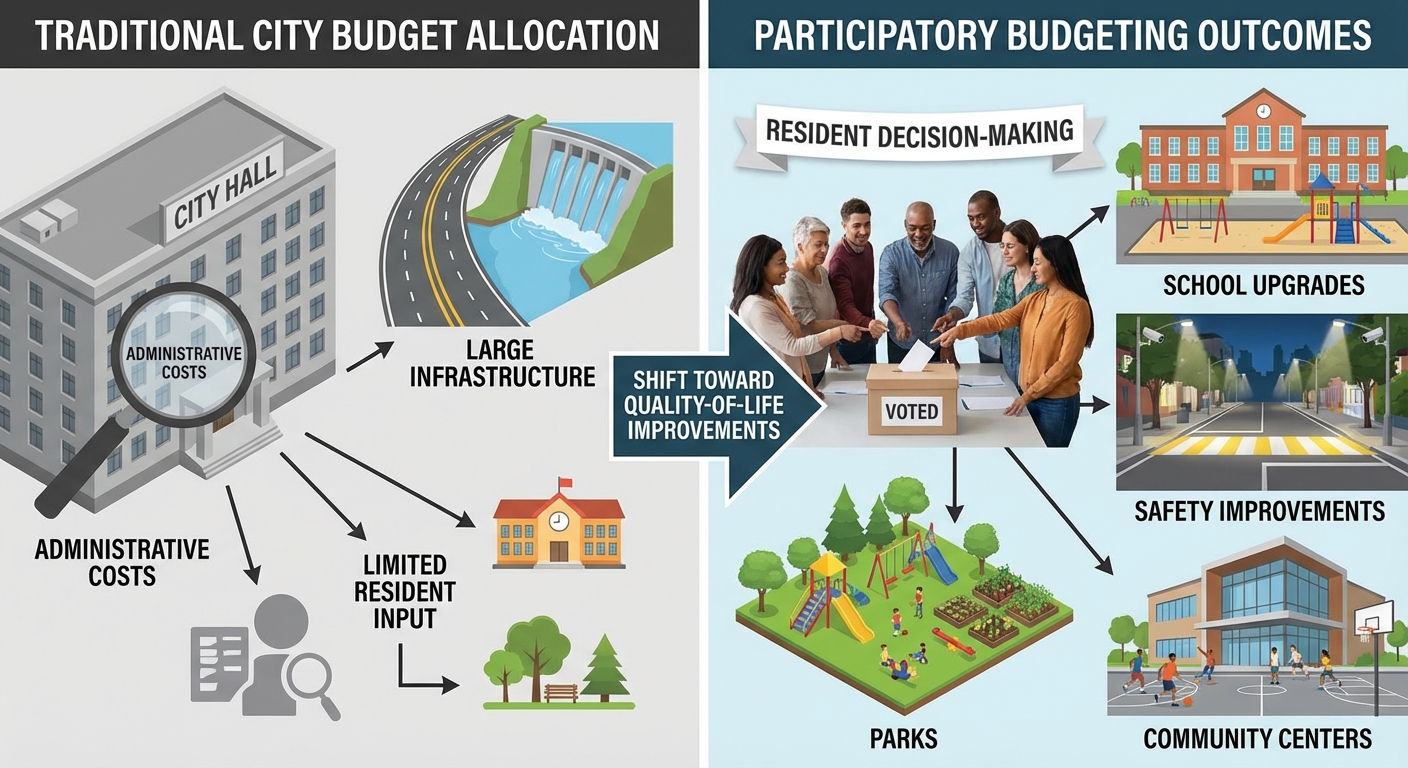

In typical city budgeting, elected officials and administrators decide how to spend your tax dollars behind closed doors. Citizens might attend public hearings, but actual decisions happen in rooms most residents never enter. Participatory budgeting flips this model completely.

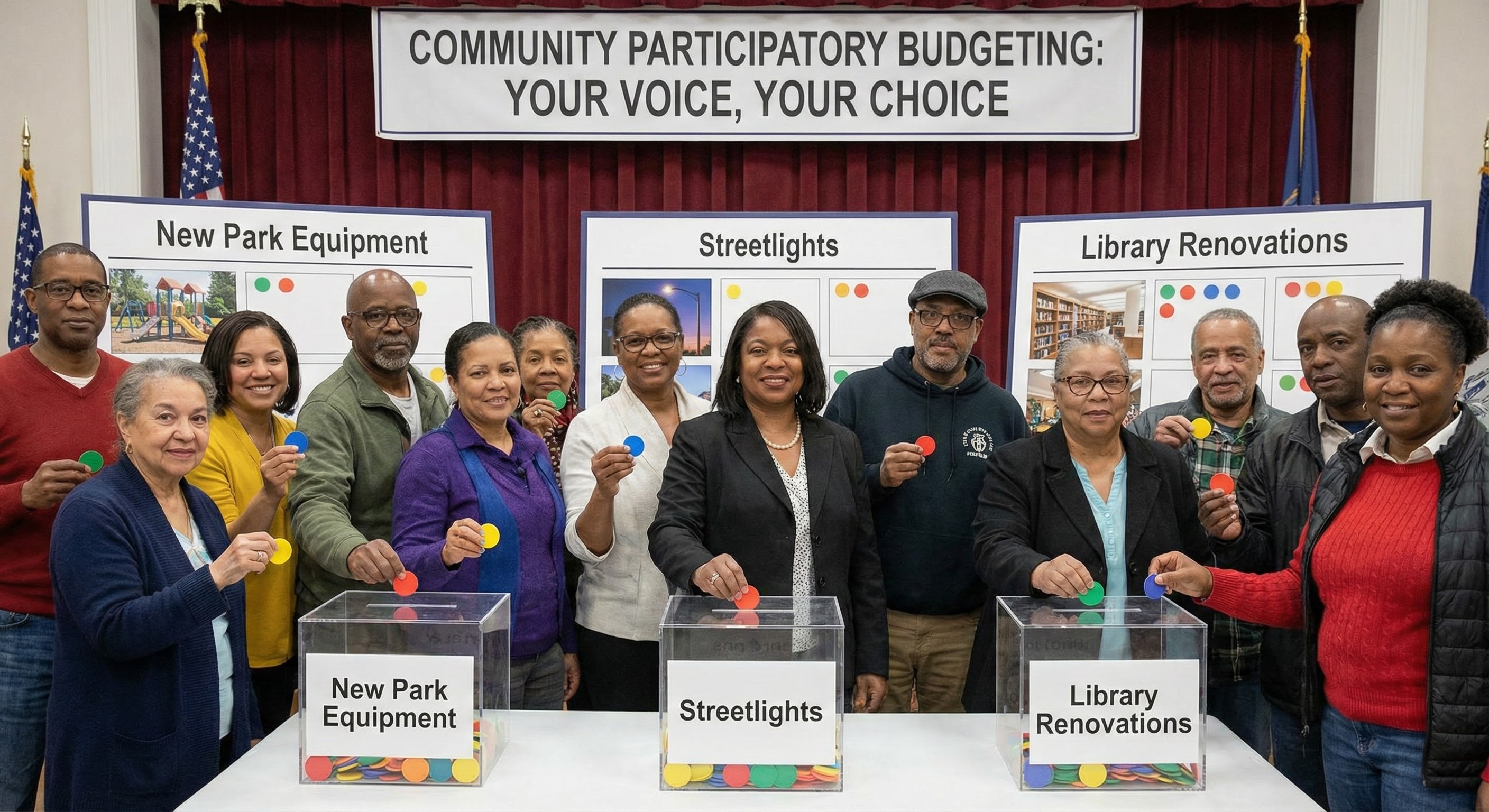

Cities allocate a portion of their budget, usually $1-5 million, and let residents vote directly on how to spend it. Playground equipment, better street lighting, public art, whatever the community wants. Residents propose ideas, volunteer committees evaluate them, and the community votes. Over 100 U.S. cities now practice this, and it’s producing surprising results.

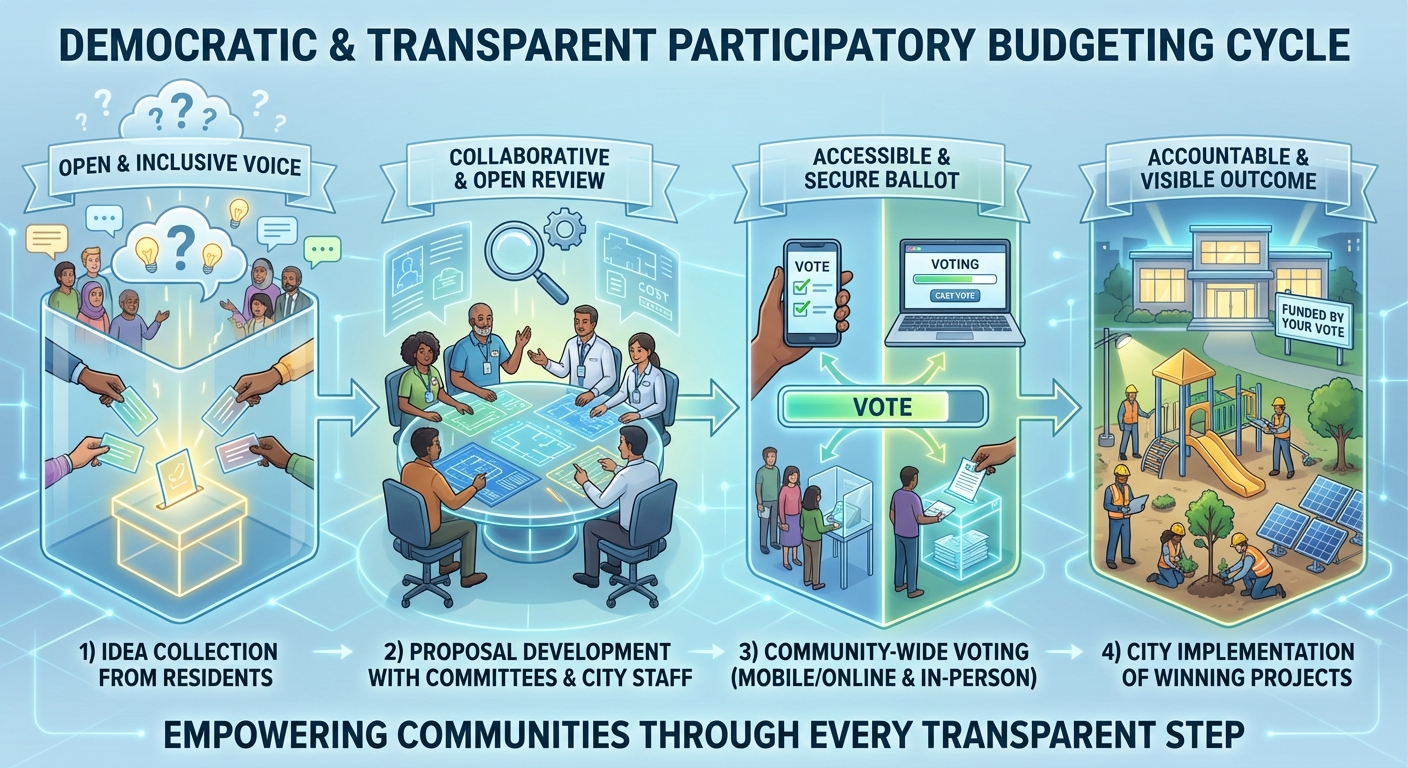

How It Works

The process typically takes 4-8 months. First, idea collection: residents submit proposals via online forms or community meetings. Unlike bureaucratic planning, almost anyone can propose a project within budget constraints. Then volunteer budget delegates work with city staff to evaluate feasibility, estimate costs, and ensure legal compliance. This vets rough concepts into concrete projects with clear price tags.

Once proposals are finalized, the community votes. Cities often use inclusive rules, allowing residents as young as 14-16, sometimes even non-citizens, to participate. Technology has supercharged this phase. Platforms like Decidim and mobile voting apps let thousands vote from smartphones, removing geographic barriers.

What Changes

The most striking result is engagement volume. A standard city council meeting draws a few dozen people. Participatory budgeting processes in New York engage 50,000-100,000 residents annually. Chicago and Phoenix see similar participation. The demographic profile is notably more diverse than typical voters: higher representation from low-income residents, people of color, and youth.

When these groups decide spending, priorities shift. Traditional budgets favor large infrastructure maintenance and administrative costs. Residents consistently vote for granular quality-of-life improvements: school upgrades like laptops and air conditioning, safety measures like streetlights and crosswalks, community assets like parks and senior centers. This reveals preference for tangible, immediate benefits over grand capital projects politicians favor.

The Challenges

Despite success, participatory budgeting faces resistance. The scale remains small, usually 1-5% of total city budgets, leaving most spending in traditional hands. The process is time-consuming for volunteers and can create localized inequality where organized neighborhoods secure more funding than less engaged ones. While diversity beats council meetings, it can still skew toward those with time and education to navigate the process.

The biggest hurdle is political will. Implementing this requires elected officials to voluntarily give up control over discretionary spending, power central to their political influence. It reduces their ability to direct funds to allies or pet projects. Consequently, participatory budgeting thrives mainly in cities with progressive coalitions philosophically committed to direct democracy, rarely in conservative administrations.

The Bottom Line

Participatory budgeting proves citizens are willing and able to make complex financial decisions when given power to do so. While limited in scale, it engages thousands and produces visible results. In an era of declining institutional trust, a process that directly involves residents and delivers tangible outcomes is a rare democratic bright spot. The concept originated in Brazil and has spread to thousands of cities worldwide, teaching that sustained commitment works better than one-off experiments. For more on how citizens are pushing back against traditional political structures, see the independent voter surge. And for another example of bottom-up civic innovation, check out Houston’s approach to homelessness.

Sources: Participatory Budgeting Project, municipal government reports, civic engagement research.