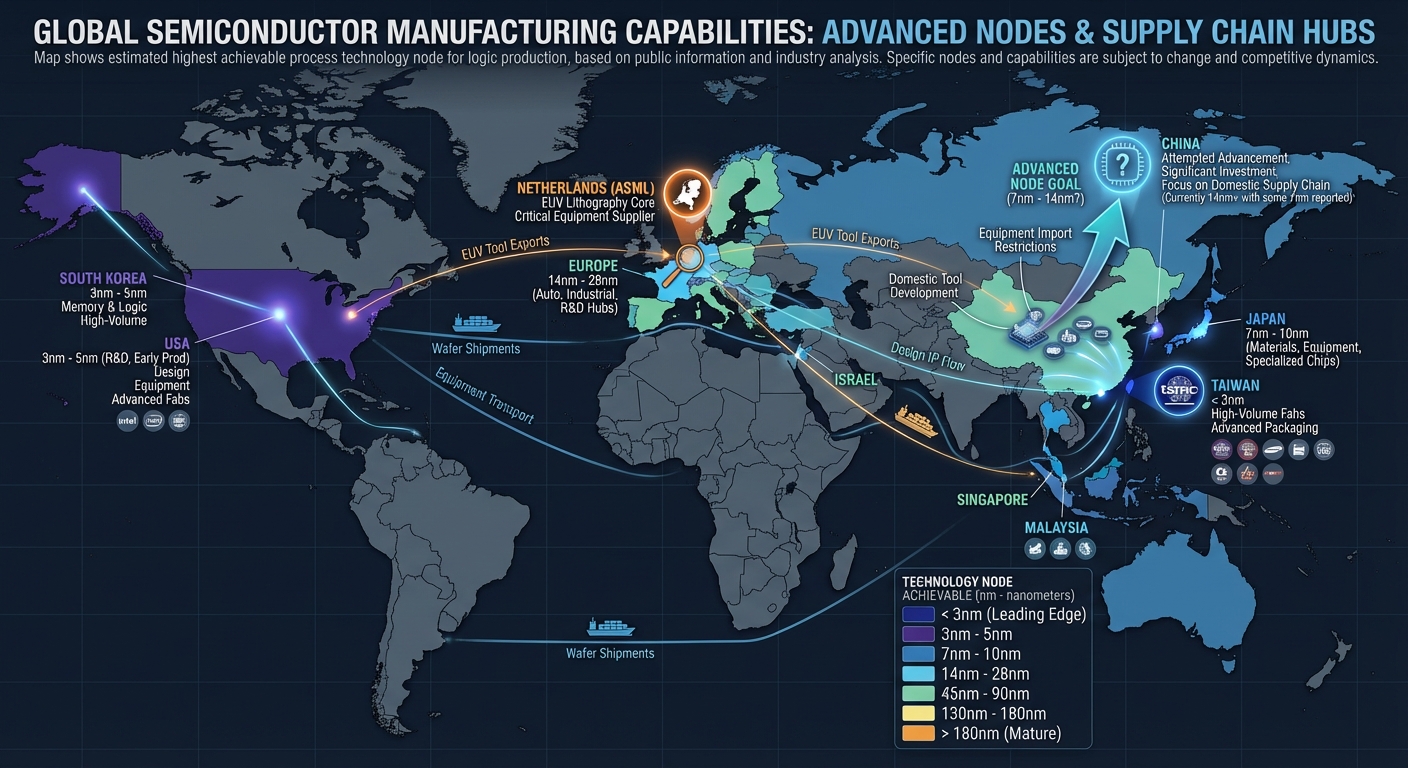

For years, the West’s most effective weapon against Chinese technological advancement hasn’t been a missile or a tariff. It’s been a machine. ASML, the Dutch company with a near-total monopoly on extreme ultraviolet lithography equipment, makes the only devices capable of producing the world’s most advanced semiconductors. Export controls have blocked China from buying them since 2019. Now, according to a Reuters investigation, China has built one of its own.

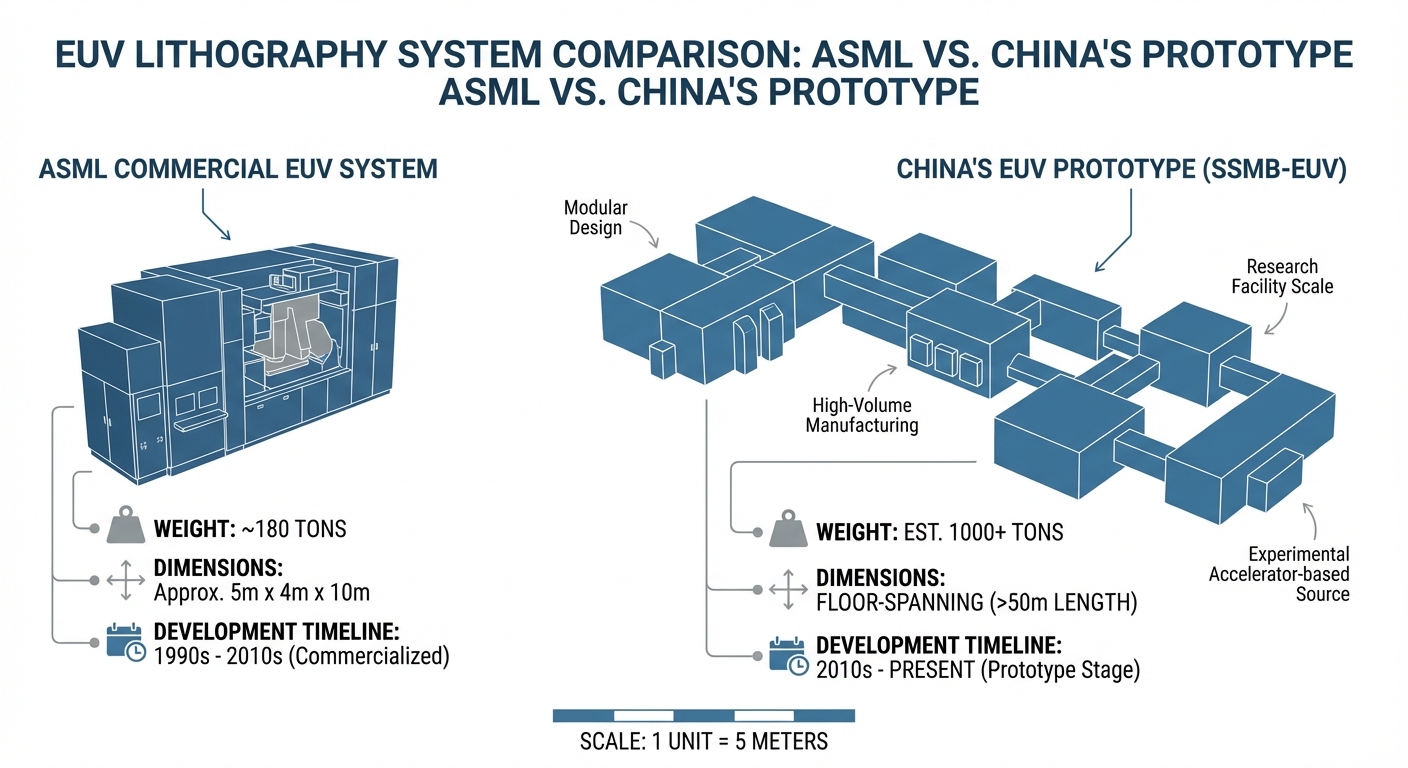

The prototype, completed in early 2025, occupies nearly an entire factory floor in a secret facility in Shenzhen. It can generate EUV light, the critical capability that makes advanced chip production possible. It has not yet produced a functioning chip, and engineers estimate it won’t be fully operational until 2028 at the earliest. But its mere existence represents a watershed moment in the global semiconductor competition, demonstrating that export controls can delay but not permanently prevent technological diffusion.

Inside the Manhattan Project for Chips

The scope of China’s effort rivals the secrecy and scale of America’s original atomic bomb program. According to Tom’s Hardware, the Shenzhen project has been running for six years as part of a broader national semiconductor strategy overseen by Ding Xuexiang, chairman of the Communist Party’s Central Commission for Science and Technology.

The stealth was extreme even by Chinese government standards. Engineers working on the project were issued fake identification documents to prevent foreign intelligence services from detecting an unusual concentration of semiconductor specialists in one location. The facility itself was designed to avoid the signatures that satellite reconnaissance typically uses to identify advanced manufacturing sites.

ASML’s commercial EUV systems weigh about 180 tons and represent perhaps the most complex machines ever built by humans. China’s prototype is far larger, sprawling across the factory floor because engineers couldn’t match the original’s compact design. “What the Chinese lab has cannot even put the light on a wafer yet,” one industry analyst told TrendForce, noting that ASML could do that in 2006, more than a decade before shipping its first commercial system.

The Brain Drain That Made It Possible

The prototype exists because China successfully recruited key talent from ASML and its supply chain. According to reports from Interesting Engineering, Beijing has run aggressive headhunting campaigns since 2019, offering semiconductor specialists signing bonuses of 3 to 5 million yuan (up to $700,000) plus housing subsidies.

The most significant catch was Lin Nan, ASML’s former head of light source technology. The light source is arguably the most challenging component of an EUV system, requiring an incredibly precise mechanism to vaporize tin droplets with laser pulses 50,000 times per second, generating the extreme ultraviolet light that etches circuit patterns onto silicon wafers. Lin’s Shanghai-based research team has filed eight patents on EUV light sources in just 18 months, according to WebProNews.

Beyond individual recruits, Huawei has emerged as the coordinator of a nationwide network involving thousands of engineers across companies and state research institutes. As reported by Cryptopolitan, Huawei has deployed staff to offices, fabrication facilities, and research centers throughout China to support the EUV effort, lending its experience with advanced technology development and its well-honed ability to work around Western restrictions. This comes as China develops new university programs focused on AI and robotics to build the next generation of technical talent.

The Technical Gaps That Remain

Having a prototype that generates EUV light is not the same as having a machine that produces chips. Several critical barriers remain, and each one could take years to overcome.

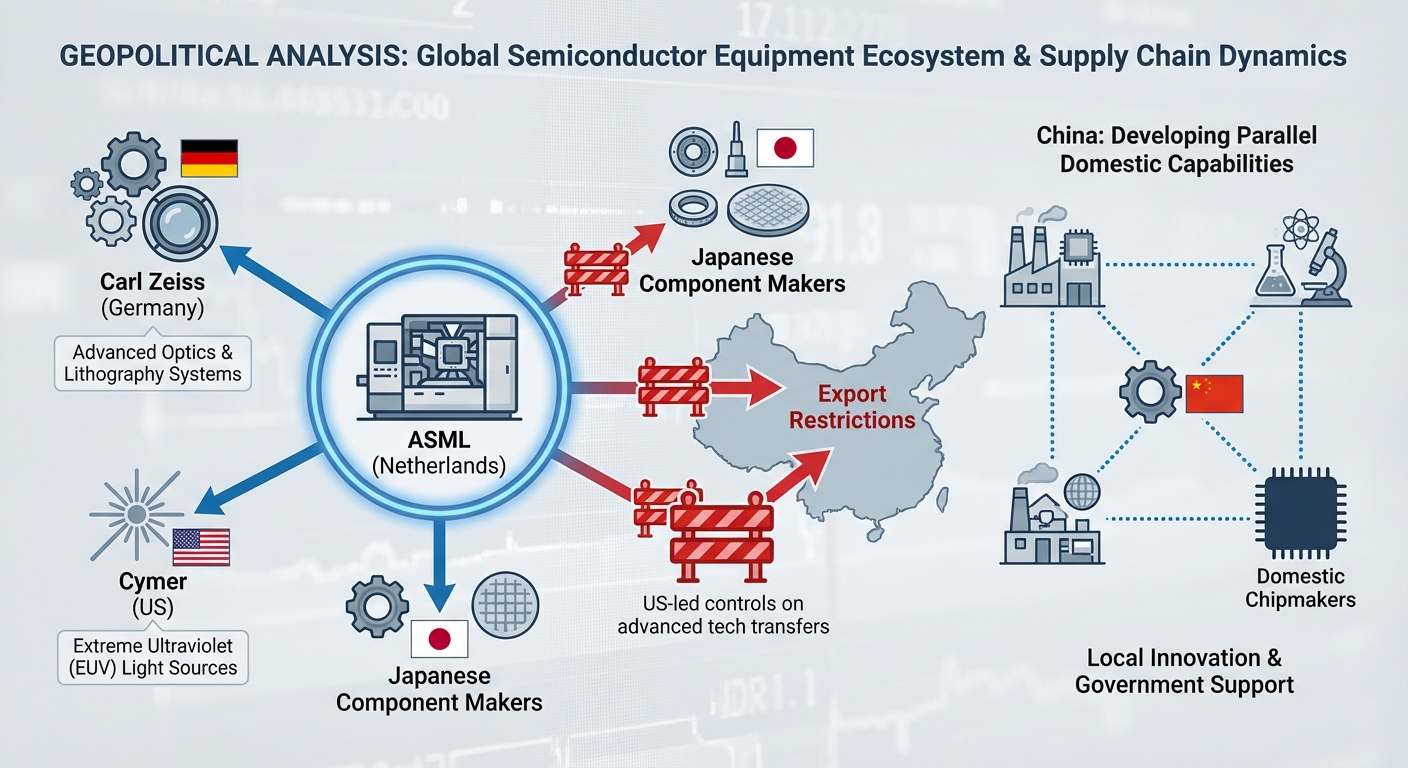

The most significant obstacle is precision optics. ASML’s systems rely on mirrors made by Germany’s Carl Zeiss AG, ground to atomic-level smoothness and coated with specialized materials. These mirrors must be accurate to within fractions of a nanometer across their entire surface, roughly the equivalent of polishing a surface the size of Germany until no bump is higher than a blade of grass. Export controls prevent China from purchasing Zeiss optics, and according to Militarnyi, China has struggled to replicate them domestically.

The prototype reportedly uses some export-restricted components from Japan’s Nikon and Canon, suggesting either stockpiling before restrictions took effect or procurement through gray market channels. However it was obtained, the reliance on foreign components creates vulnerability. A truly indigenous EUV capability would require domestic alternatives for every critical part.

Project participants quoted in the Reuters investigation believe 2028 is an optimistic target for producing working chips, with 2030 more realistic. By that time, the semiconductor industry will likely have moved on to high-NA EUV, the next generation of lithography technology that ASML is already developing. China’s breakthrough, when it comes, may already be a generation behind.

Why This Matters Beyond Chips

The strategic implications extend far beyond consumer electronics. The most advanced semiconductors power military systems, artificial intelligence, and critical infrastructure. The United States has explicitly framed chip export controls as a national security measure, arguing that limiting China’s access to cutting-edge chips constrains its military modernization. Meanwhile, American companies are racing to develop alternatives to Nvidia’s dominance, including Amazon’s Trainium chips designed for AI workloads.

If China can produce EUV machines domestically, even inferior ones, it would undermine the foundation of that strategy. Chips made on domestic equipment, even slightly less advanced chips, would be immune to export controls. China could equip its military, power its AI research, and build its surveillance infrastructure without depending on Western supply chains.

The timeline matters enormously here. Every year China spends catching up is a year the West maintains its advantage. The question is whether that advantage can be leveraged into something more durable than a temporary lead in a specific technology.

The Lessons Being Drawn

Different observers are taking different lessons from China’s EUV breakthrough. For advocates of aggressive export controls, the six-year timeline validates the approach: it has taken enormous effort and resources for China to reach even a prototype stage, time that has allowed Western companies to extend their leads and Western militaries to stockpile advanced equipment.

For skeptics of export controls, the prototype demonstrates the limits of technology denial. Determined adversaries with significant resources will eventually overcome restrictions, and in the meantime, those restrictions create strong incentives for self-sufficiency that might not otherwise exist. China’s semiconductor industry, while still behind global leaders, is far more capable than it was in 2019 when EUV restrictions took effect.

The role of human capital highlights a tension in technology policy. The engineers who built China’s EUV prototype learned their skills at Western companies. Many are Chinese nationals who studied abroad, worked for ASML or its suppliers, and then returned home with knowledge that no export control can block. Restricting chip exports is relatively straightforward compared to restricting human movement and knowledge transfer. The competition for AI talent is playing out globally, with billions being invested in India’s AI infrastructure and similar efforts underway across Asia.

The Bottom Line

China has built a prototype EUV lithography machine, the first outside the ASML-dominated Western supply chain. It took six years, massive resources, fake IDs for engineers, and the recruitment of key talent from the company it was copying. The machine doesn’t work yet, it’s far larger than the commercial version, and it may not produce chips until 2028 or later.

But it exists. And in the context of the global semiconductor competition, that existence alone changes the calculus. Export controls bought time. They did not buy permanent advantage. What the West does with that time, whether it maintains its lead or watches it erode, will shape the technological balance of power for decades to come.

The chip war continues, but the front lines just shifted.

Sources: TechSpot, Tom’s Hardware, TrendForce, Interesting Engineering, WebProNews, Militarnyi.