Your local veterinary clinic was bought by a private equity firm. Prices doubled, the vets you trusted left, and the service now feels corporate and rushed. Your favorite restaurant chain cut portion sizes and switched to cheaper ingredients after an acquisition. Your apartment complex is now owned by a faceless LLC that raises rents while ignoring maintenance.

Private equity has become one of the most powerful and disliked forces in the American economy, controlling $5.8 trillion in assets and owning thousands of companies that affect your daily life. Most people know that when private equity buys a business, it usually gets worse for customers and employees. But few understand the specific financial mechanics that drive this decline.

It isn’t just greed. It’s a business model designed to extract value in ways that often destroy the underlying asset.

The Leveraged Buyout Mechanism

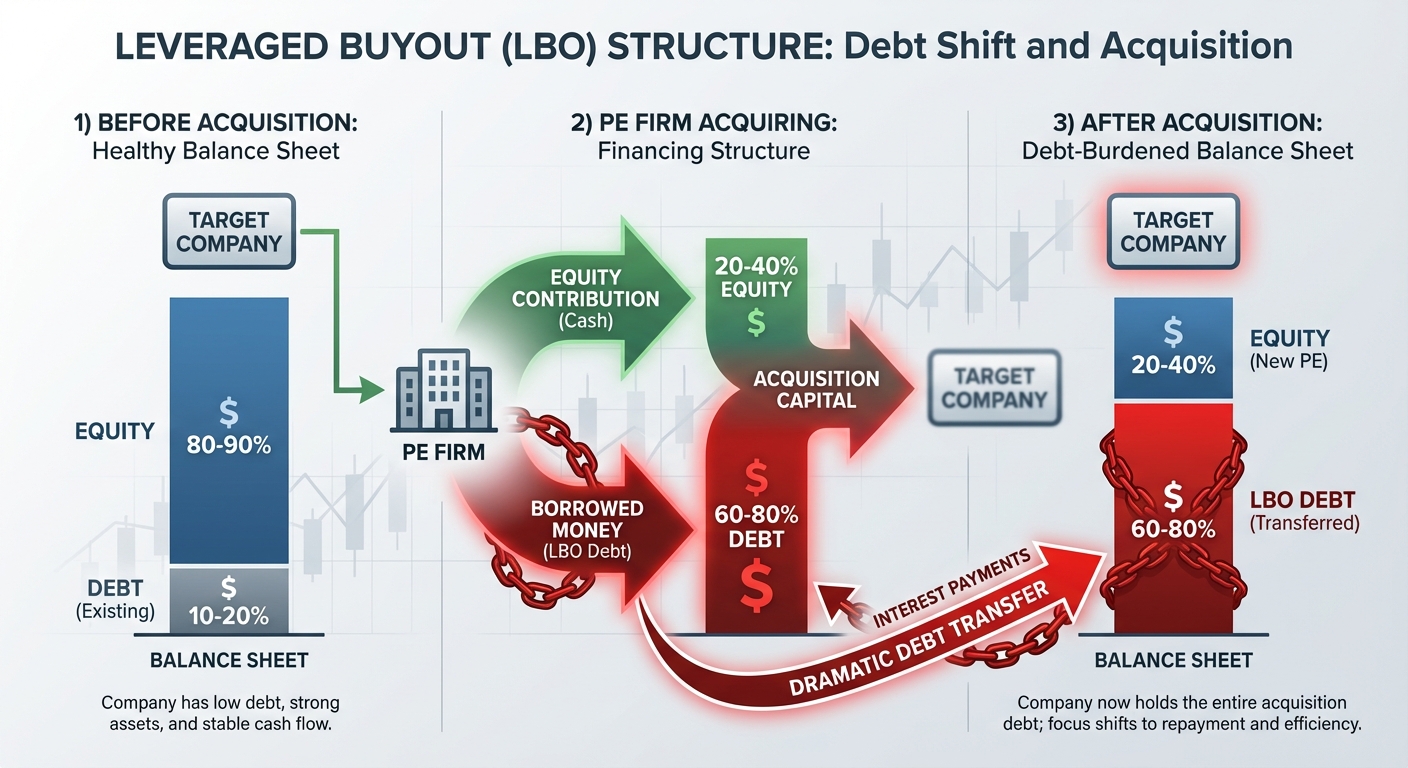

The core of the private equity model is the Leveraged Buyout (LBO). A PE firm buys a company using a small amount of its own money (usually 20-40%) and a massive amount of borrowed money (60-80%). Crucially, this debt is placed on the company’s balance sheet, not the PE firm’s.

Imagine buying a house where you put down a down payment, but the house itself is responsible for paying the mortgage. If the house can’t pay, the bank takes it, but your other assets are safe. That’s how PE works.

The acquired company is suddenly saddled with enormous debt payments it didn’t have before. To service this debt, it must aggressively cut costs, raise prices, or sell off assets. This financial pressure forces the degradation of service and quality that consumers hate. The company didn’t choose this debt, it was imposed by the new owners.

Why Quality Always Declines

The incentives are misaligned with long-term health. PE firms typically hold companies for only 3-7 years before selling them. They need to boost financial metrics quickly to maximize the sale price. This encourages short-term thinking: firing experienced staff to cut payroll, deferring maintenance, or selling real estate and leasing it back for a quick cash infusion.

These moves look great on a quarterly spreadsheet but gut the company’s long-term viability. When customer satisfaction drops or employee expertise disappears, that’s a problem for the next owner, not the PE firm that already sold and moved on.

The Toys R Us case is the quintessential example. In 2005, it was bought by PE firms that loaded it with $5.3 billion in debt. The company was profitable operationally, but it had to spend over $400 million a year just to pay interest on that debt. This crippled its ability to invest in stores or e-commerce to compete with Amazon. Eventually, it collapsed, costing 33,000 people their jobs. The PE firms, however, had already extracted hundreds of millions in fees.

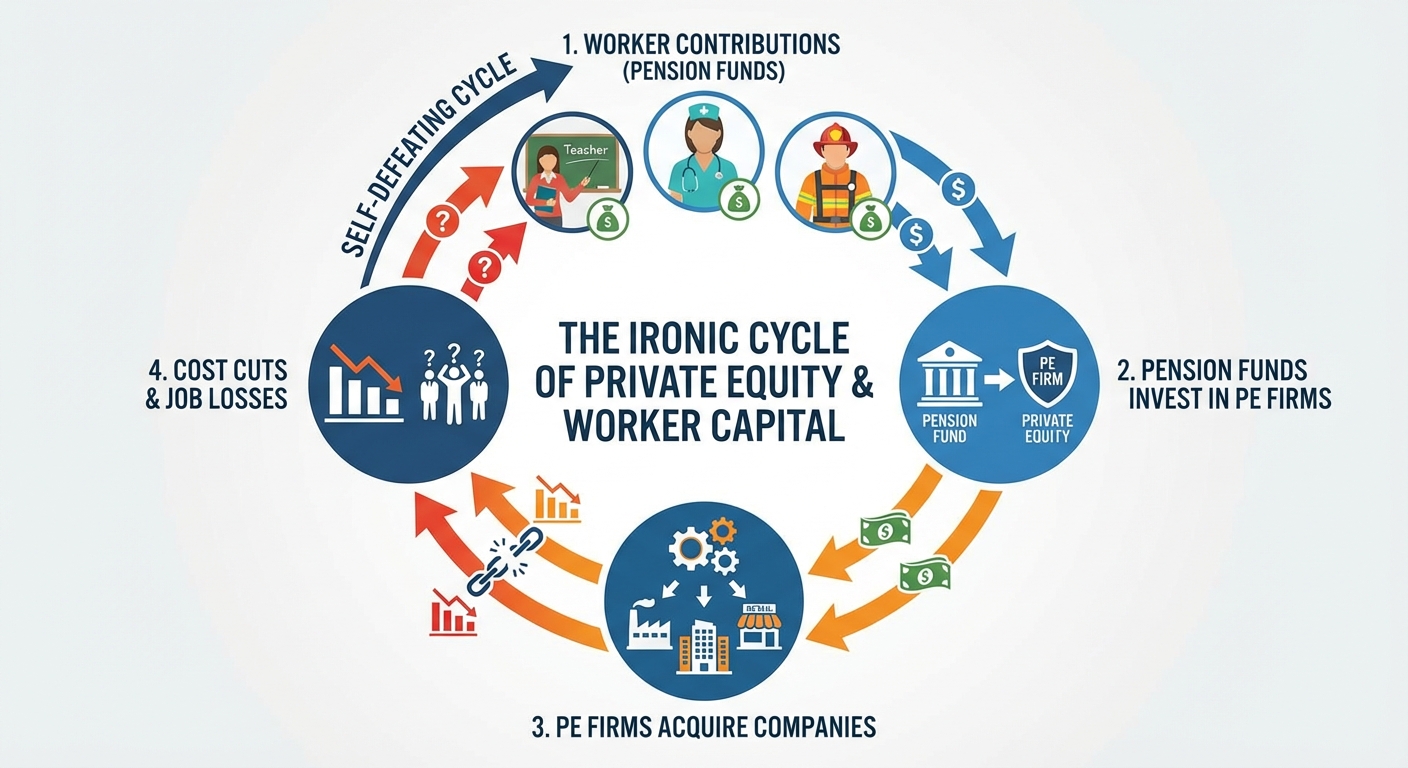

The Pension Fund Irony

Here’s the bitter irony: the money fueling private equity often comes from pension funds for teachers, firefighters, and nurses. These funds invest in PE because it promises high returns needed to pay retirees. So, the workers’ own retirement savings effectively fund the firms that buy their employers, cut their benefits, and outsource their jobs.

It’s a system that eats itself. Unlike boring businesses where owner-operators have skin in the game long-term, PE firms are optimizing for a quick flip. The model works incredibly well for investors and firm partners. It works terribly for the businesses they buy, the employees who work there, and the customers they serve.

What Needs to Change

Until regulations change to align incentives or limit debt loading, the playbook will continue: buy, borrow, cut, flip, and leave someone else to clean up the mess. Some proposed reforms include limiting the amount of acquisition debt that can be placed on target companies, requiring PE firms to hold companies longer before selling, or increasing transparency about fees extracted.

But the PE industry has powerful lobbying influence, and many politicians benefit from PE campaign contributions. Change will be slow. In the meantime, when you hear that your favorite local business was “acquired by a private equity firm,” you now know what that probably means for quality, service, and prices.

The Bottom Line

Private equity isn’t inherently evil, it’s just optimized for outcomes that don’t align with long-term business health or stakeholder wellbeing. The model excels at extracting value quickly, which is exactly what it’s designed to do. Understanding the mechanics helps you see why corporate strategies matter and why some business models prioritize long-term sustainability over short-term extraction.

The next time your service gets worse after an acquisition, it’s not incompetence. It’s the playbook working exactly as designed.

Sources: Private equity industry analysis, LBO case studies, pension fund investment data.