If you’ve spent more than five minutes on social media this year, you already understand why Oxford University Press just named “rage bait” its 2025 Word of the Year. The term refers to online content “deliberately designed to elicit anger or outrage by being frustrating, provocative” in order to drive engagement and traffic. In other words, the exact kind of post that makes you hate-click before you can stop yourself.

Oxford’s selection, announced Monday, beat out finalists including “looksmaxxing” (the practice of optimizing one’s physical appearance) and “brainrot” (the deterioration of mental state from consuming low-quality online content). The selection comes as Australia enacted its own social media ban for minors, reflecting growing global concern about online platforms. That the dictionary had to choose between three terms describing different flavors of internet dysfunction tells you everything about where we are as a digital society.

Why ‘Rage Bait’ Won

The selection committee cited the term’s rapid adoption across platforms and its precise capture of a phenomenon that has fundamentally shaped online discourse in 2025. Unlike previous words of the year that reflected cultural moments or new technologies, “rage bait” describes a deliberate manipulation strategy that has become central to how content spreads online.

“Rage bait represents a shift in how we think about online content creation,” said Casper Grathwohl, president of Oxford Languages, in the announcement. The term acknowledges that much of what appears in our feeds isn’t meant to inform or entertain. It’s engineered to provoke a reaction strong enough that we can’t scroll past.

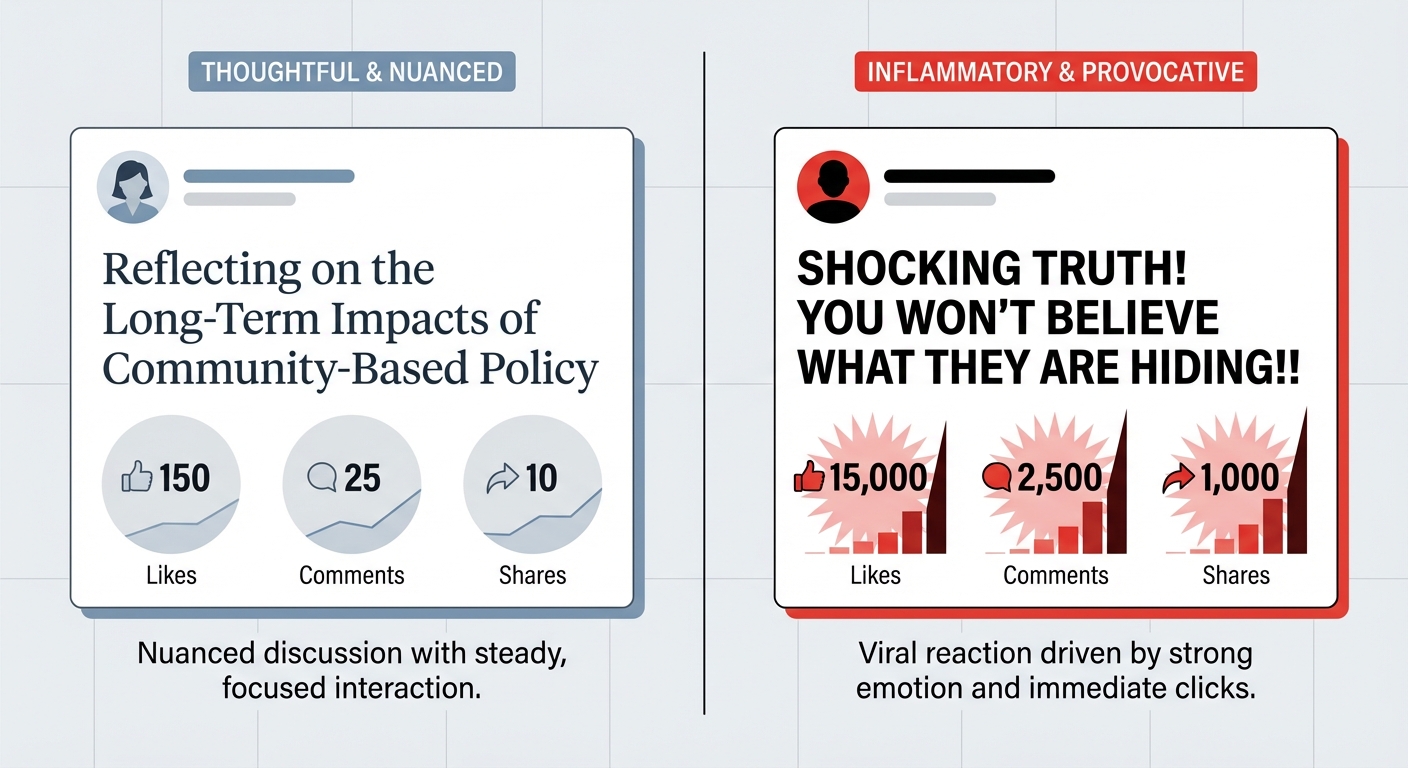

The mechanics are simple but effective. Content creators and algorithms have discovered that anger generates more engagement than almost any other emotion, a dynamic that also plagues deepfake detection efforts as outrage-inducing fake content spreads faster than corrections. Angry users comment more, share more, and spend more time on platforms arguing in threads. For platforms built on engagement metrics, rage is good business.

The Business Model Behind the Outrage

This isn’t a new phenomenon, but 2025 marked the year it became impossible to ignore. A study published in September by the Pew Research Center found that posts containing inflammatory language received 73% more engagement than neutral content on average. For creators competing for visibility in algorithm-driven feeds, the incentive structure is clear.

The pattern extends beyond individual creators. Major publishers have restructured headlines and content strategies around outrage potential. Political operatives on both sides have embraced rage bait as a fundraising tool, with inflammatory emails generating substantially higher donation rates than informational ones. The strategy is central to how AI is reshaping political campaigns, where algorithms optimize for emotional response. Even brands have experimented with controversy as a marketing strategy, calculating that angry attention is still attention.

The consequences extend beyond wasted time and elevated blood pressure. Researchers at Stanford’s Internet Observatory have linked the rise of rage bait to increased political polarization, noting that algorithmically amplified outrage tends to present the most extreme versions of opposing viewpoints. When your understanding of the other side comes primarily from content designed to make you angry, productive dialogue becomes nearly impossible.

What Happens Now

The selection of “rage bait” as Word of the Year won’t change the economics driving the phenomenon. But language matters, and having a precise term for what’s happening represents a form of collective recognition. You can’t solve a problem you can’t name.

Platform companies have begun acknowledging the problem, though solutions remain elusive. Meta announced earlier this year that it would reduce the algorithmic boost given to content that generates primarily angry reactions, though critics note the company hasn’t released data on the policy’s effectiveness. TikTok has experimented with friction features that prompt users to pause before sharing certain content.

The timing of Oxford’s announcement feels appropriate. As we enter 2026, there’s growing recognition that the attention economy’s incentive structures need rethinking. The question is whether that recognition will translate into meaningful change, or whether “rage bait” will simply describe our online experience for years to come.

The Bottom Line

Oxford’s choice reflects an uncomfortable truth about the current state of digital communication. The most effective way to capture attention online is often to make people angry, and the systems we’ve built reward exactly that behavior. “Rage bait” entering the official lexicon is less a celebration and more a diagnosis. The first step toward treatment is acknowledging the problem. Whether we’re ready for the next steps remains to be seen.

Sources: Oxford University Press, Pew Research Center, Stanford Internet Observatory.