The Federal Reserve kicks off its final meeting of 2025 today, and if you’re wondering whether to lock in that mortgage rate or refinance your car loan, here’s what you need to know: another rate cut is coming, but what the Fed says about 2026 matters more than the cut itself. Markets are pricing in a 90% probability of a quarter-point reduction when the central bank announces its decision Wednesday, which would mark the third consecutive cut since September and bring the federal funds rate to a range of 4.25% to 4.5%.

But the bigger story isn’t what happens this week. It’s what Fed Chair Jerome Powell signals about the pace of cuts next year. With inflation proving stickier than expected and labor market data sending mixed signals, the Fed’s balancing act is getting more complicated. Traders are growing anxious about whether 2025’s steady cadence of rate cuts will continue or slow dramatically in 2026.

Why Another Cut Is All But Certain

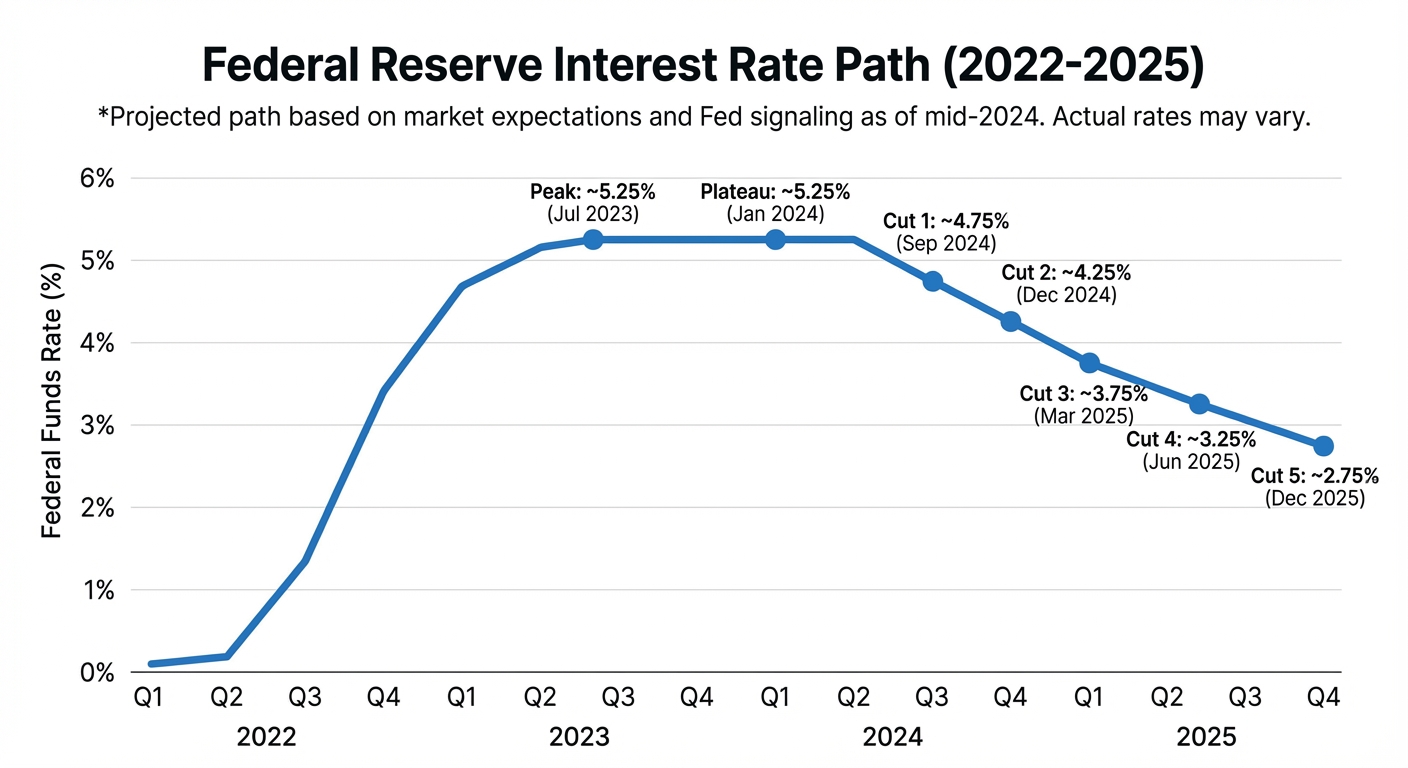

The Fed has been on a clear path since pivoting to rate cuts in September. After holding rates at a 23-year high for over a year to combat inflation, the central bank cut by half a percentage point in September, followed by quarter-point cuts in November. Another quarter-point cut this week would be consistent with that trajectory and align with the Fed’s goal of gradually returning rates to a “neutral” level that neither stimulates nor restricts economic growth.

The case for cutting is straightforward. Inflation, while still above the Fed’s 2% target, has fallen dramatically from its 2022 peak of over 9%. The labor market, though resilient, is showing signs of cooling. Job openings data released today showed 7.67 million openings in October, above expectations but still well below the 12 million peak of 2022. The Fed wants to ease policy while it can, before the economy weakens further.

What makes this meeting interesting isn’t the decision itself but the context around it. The FOMC will release updated economic projections, including the closely watched “dot plot” that shows where individual Fed officials expect rates to be in the coming years. In September, the median projection showed rates falling to about 3.4% by the end of 2025 and 2.9% by the end of 2026. Markets will scrutinize whether those projections hold or get revised upward.

The Complicating Factors

Not everything is pointing toward aggressive rate cuts. November’s jobs report showed the economy added 227,000 jobs, above expectations, suggesting the labor market isn’t weakening as fast as some feared. Meanwhile, ADP’s private payroll report showed the private sector unexpectedly lost 32,000 jobs, creating conflicting signals about employment trends.

Inflation remains the wildcard. While headline inflation has fallen, core measures that exclude volatile food and energy prices have been sticky. The Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, remains above 2.5%, and some components like shelter costs continue to run hot. Several Fed officials have publicly expressed concern about cutting too quickly and reigniting inflation.

Then there’s the political dimension. Trump’s Fed chair pick has already rattled markets. President-elect Trump has been vocal about wanting lower interest rates, creating potential tension with the Fed’s independence. Powell has repeatedly stated that the Fed makes decisions based on economic data, not political pressure, but the dynamic adds uncertainty to the outlook.

What It Means for Your Money

If you have a variable-rate mortgage, credit card debt, or an adjustable-rate loan, you’ve likely already seen your costs decline slightly since September. Another quarter-point cut means another modest reduction in what you’re paying. On a $400,000 variable-rate mortgage, a 25-basis-point cut typically translates to about $50 per month in savings.

For savers, the news is less positive. High-yield savings accounts and certificates of deposit, which offered attractive rates during the Fed’s hiking cycle, will continue to see yields decline. If you’ve been parking cash in a money market fund yielding 5%, that rate is heading toward 4% and could go lower.

The housing market is watching closely. Mortgage rates, which peaked above 8% in late 2023, have fallen to around 6.1% for a 30-year fixed loan. Further Fed cuts could push them toward 5.5% by mid-2026, potentially reigniting demand from buyers who’ve been sidelined by high borrowing costs. The AI infrastructure boom has also been sensitive to rate expectations.

The 2026 Question

Markets have largely priced in this week’s cut. What traders are really focused on is Powell’s press conference Wednesday afternoon and the signals he sends about 2026. Will the Fed continue cutting at every meeting? Will it pause to assess the impact of cuts already delivered? How worried is the central bank about inflation reigniting?

The consensus expectation is for the Fed to signal a slower pace of cuts next year, perhaps moving from every meeting to every other meeting. That would suggest three or four quarter-point cuts in 2026, rather than the six or seven cuts some optimistic forecasters had projected earlier this year.

For consumers and businesses making financial decisions, the practical implication is that rates are coming down, but probably more slowly than many hoped. The era of emergency-level rates is over, but we’re not heading back to the near-zero rates of the 2010s anytime soon.

The Bottom Line

The Fed’s December meeting is more about the message than the decision. Another quarter-point cut is essentially guaranteed, bringing rates to their lowest level since early 2023. But with inflation still above target and the labor market sending mixed signals, the central bank is navigating without a clear map.

Powell’s challenge Wednesday will be threading a needle: reassuring markets that the Fed remains committed to supporting the economy while preserving flexibility to respond if inflation proves more persistent than expected. For anyone with debt, savings, or plans to buy a home, the answer to “when will rates come down?” is clear: they already are, just not as fast as you might like.

Sources: Federal Reserve, CME FedWatch, Bureau of Labor Statistics, ADP Research Institute.