While the media tracks every move of Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, a different group of tycoons is quietly amassing fortunes in the shadows. These are the infrastructure billionaires: owners of construction firms, engineering consultancies, and material suppliers who are the primary beneficiaries of the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in 2021.

This wealth creation is decidedly unsexy. It comes from asphalt, concrete, steel, and heavy machinery. Yet families like the Hendricks (ABC Supply) have built multi-billion dollar empires. The flow of federal funds into roads, bridges, broadband, and water systems has supercharged this sector, creating a gold rush for those who own the capacity to build.

The Concrete Gold Rush

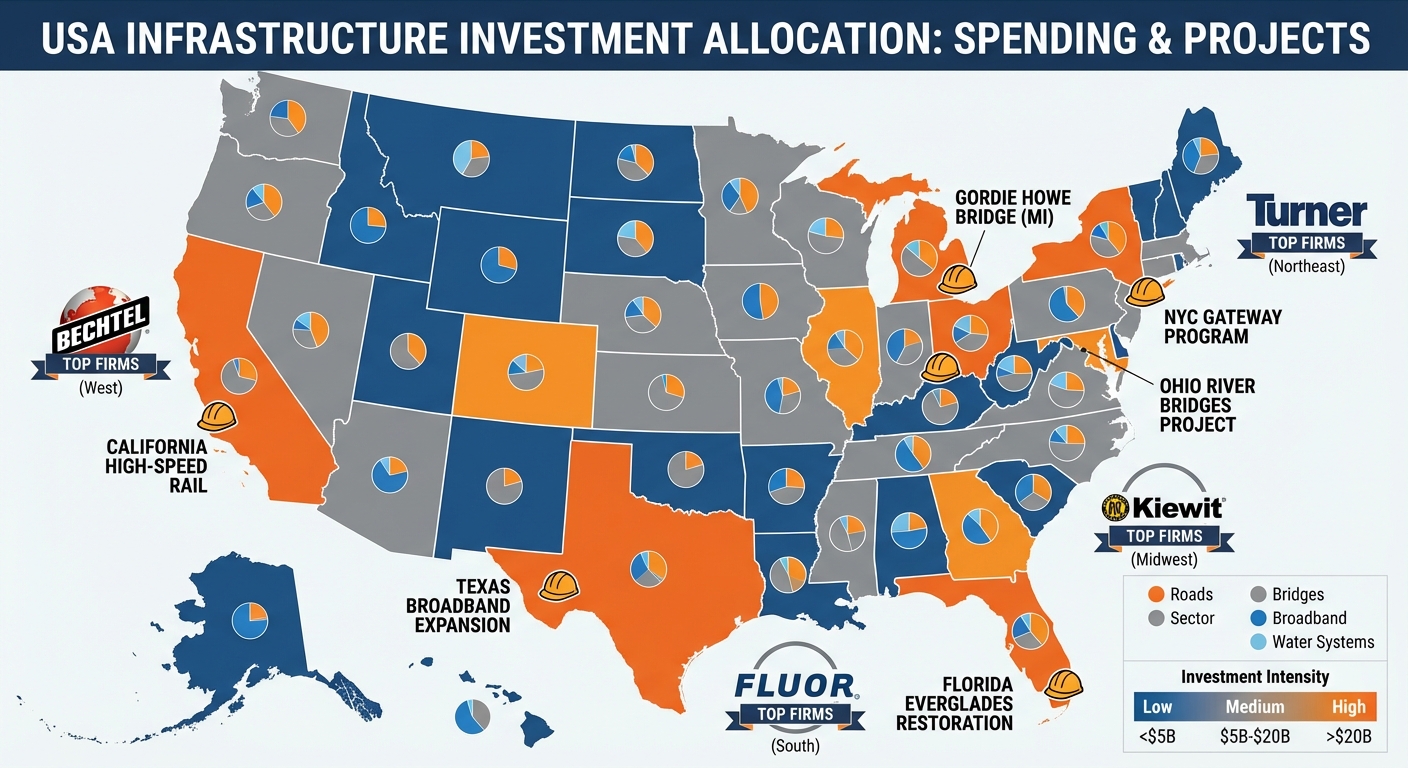

The mechanism is simple: government contracts. The infrastructure bill allocated hundreds of billions for physical upgrades. This money flows to large construction firms like Bechtel and Fluor, but also to regional players who dominate local markets.

Winning these contracts requires deep political connections, specialized equipment, and the ability to execute complex projects on time and budget. Those who succeed reinvest in capacity, buying up smaller competitors to create economies of scale. This consolidation has birthed regional monopolies in sectors like road paving and water treatment, giving owners pricing power and immense stability.

Unlike tech startups where Chief AI Officers debate strategy, infrastructure companies operate in regulated markets with government-backed revenue streams. The work is predictable, the contracts are long-term, and the cash flow is reliable.

The Private Equity Play

Private equity recognized this opportunity early. Firms have been rolling up fragmented industries like engineering consultancies, equipment rental, and specialty contractors for years. They see infrastructure as a safe asset class with government-backed revenue streams.

This financialization of the sector means that many “local” construction firms are now portfolio companies owned by massive funds, extracting value and generating returns for pension funds and wealthy investors. The private equity playbook works particularly well in infrastructure because the government contracts provide predictable cash flow to service acquisition debt.

The consolidation creates efficiency but also concentration. A handful of mega-firms now control significant portions of America’s building capacity. This gives them enormous leverage in contract negotiations and pricing, further accelerating wealth accumulation at the top.

The Generational Transfer

Unlike tech wealth, which can be created overnight, infrastructure fortunes are often multi-generational. A grandfather starts a small paving company in the 1960s. The father grows it regionally through the 1980s and 90s, winning state contracts. The grandchild sells it to private equity for $500 million in the 2020s.

It’s patient capital, built on tangible assets and essential services. In an era of digital volatility where IPO markets swing wildly, the business of building the physical world remains a reliable path to the 1%. The work is hard, the timelines are long, but the payoff is generational wealth.

Why This Matters for You

The rise of infrastructure billionaires reveals an important economic truth: government spending creates private wealth. The $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill isn’t just fixing roads, it’s minting millionaires and billionaires in construction, engineering, and materials.

For workers, this means opportunities in skilled trades. The demand for electricians, heavy equipment operators, and project managers is soaring, with wages rising accordingly. For entrepreneurs, it means opportunities in the boring but profitable businesses that support infrastructure: equipment rental, specialty contracting, materials supply.

The infrastructure boom isn’t glamorous, but it’s one of the most significant wealth creation events of this decade. While everyone watches tech, the real money might be in concrete and steel.

The Bottom Line

America’s newest billionaires aren’t coding apps or launching rockets. They’re pouring concrete, laying asphalt, and building the physical infrastructure that makes modern life possible. The media won’t profile them, but their bank accounts don’t care.

The infrastructure bill created a 10-year gold rush for those positioned to capture it. The companies that own the equipment, the expertise, and the political connections are printing money. And unlike tech companies burning billions on speculative bets, infrastructure firms are getting paid by the government to do work that absolutely needs to be done.

Unsexy? Absolutely. Profitable? Incredibly. The hidden billionaires are building more than infrastructure. They’re building dynasties.

Sources: U.S. Department of Transportation, Forbes, Associated General Contractors of America.