If you’ve been waiting for interest rates to plunge back to pandemic-era lows, 2026 is going to disappoint you. But if you’ve been worried about a recession, the news is considerably better. The Federal Reserve enters the new year with rates already down from their 2023 peaks, inflation largely under control, and an economy that continues to grow despite years of predictions that a downturn was imminent. The question for your finances isn’t whether rates are going down but rather how quickly and how far.

The Fed’s own officials project just one quarter-point rate cut this year, which would lower the federal funds rate from its current 3.5% to 3.75% range to between 3.25% and 3.5%. Markets are slightly more optimistic, pricing in two cuts. Some economists think both forecasts are too conservative. Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, expects three cuts before midyear alone, arguing that labor market weakness and political pressure will push the central bank to move faster than it currently signals.

Here’s what that means for your mortgage, your savings account, and the broader economy you’re navigating.

Where We Are Now

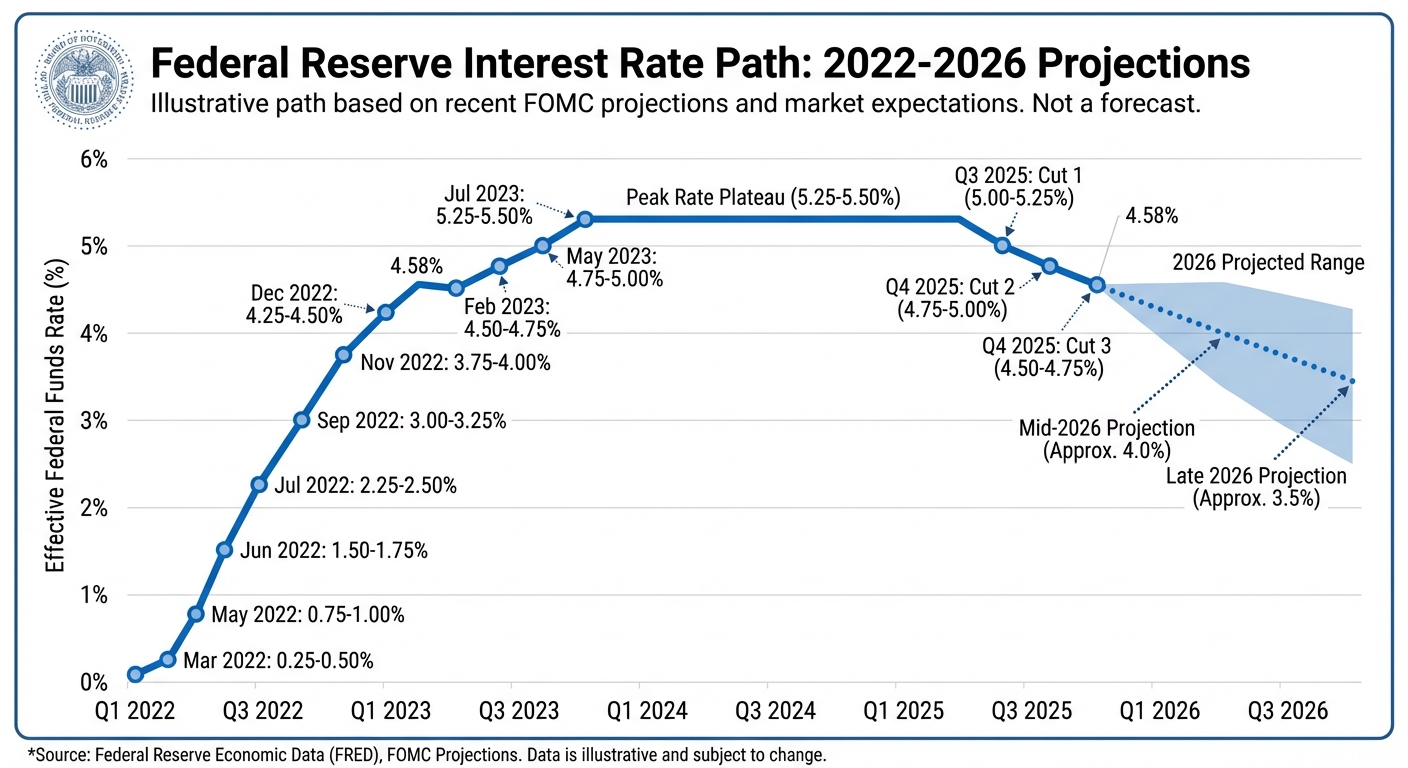

The Federal Reserve cut interest rates three times in 2025, bringing the federal funds rate down from the 5.25% to 5.5% range where it sat for most of the year to the current 3.5% to 3.75% range. That December cut capped a year in which the central bank pivoted from fighting inflation to supporting economic growth, a transition that felt overdue to borrowers and welcome to anyone hoping to buy a house or refinance debt.

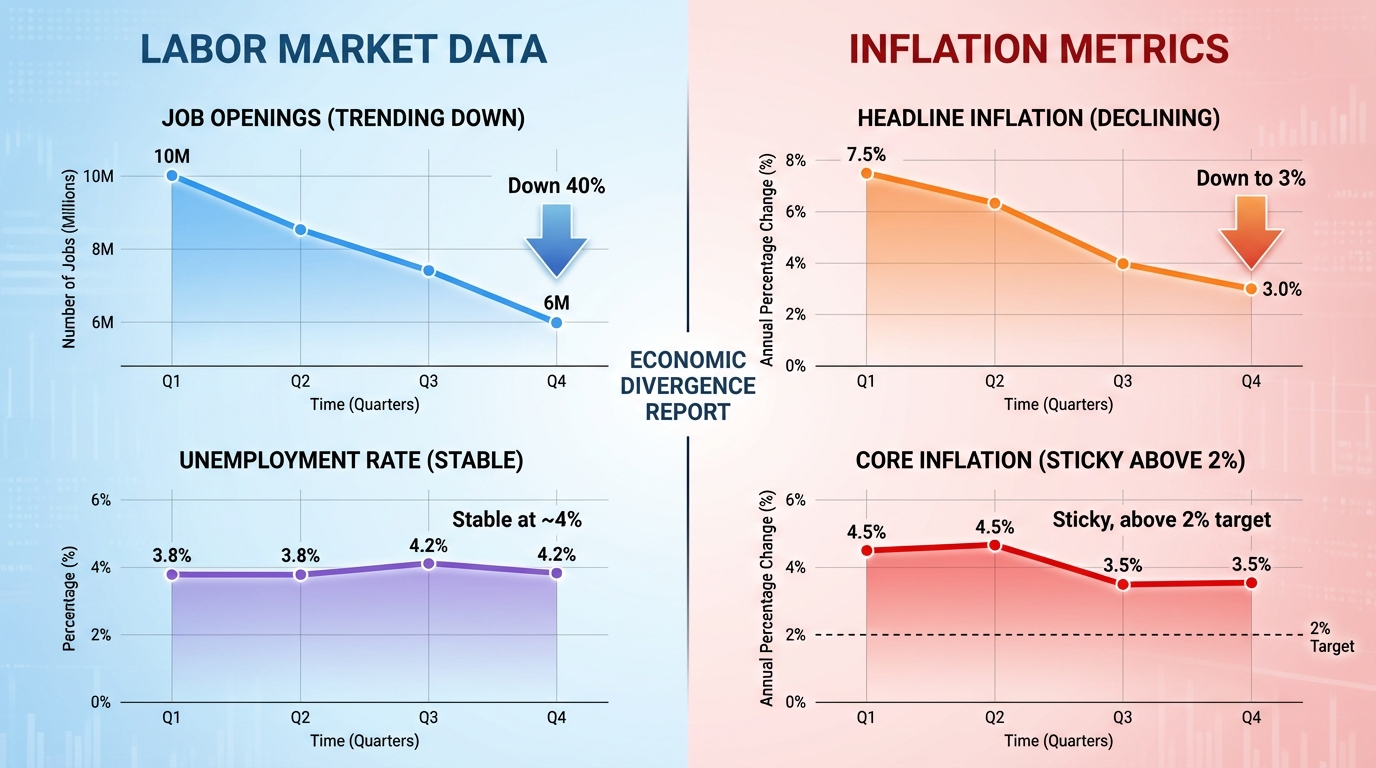

The economic backdrop justifies that shift. Inflation, as measured by the Fed’s preferred Personal Consumption Expenditures index, has fallen dramatically from its 2022 peak of over 9% to around 2.5%. That’s still above the Fed’s 2% target, but it’s close enough that central bankers feel comfortable easing policy. The labor market remains solid, with unemployment projected to end 2026 at 4.4%, roughly where it stands today.

The Fed’s official statement from December projected economic growth of 2.3% for 2026, up from the 1.8% forecast made in September. That upgrade reflects an economy that has proved more resilient than many expected. Consumer spending remains strong, business investment continues, and the labor market has avoided the sharp deterioration that some economists predicted would follow aggressive rate hikes.

Yet the picture isn’t entirely rosy. Core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, remains sticky at 2.5%. Housing costs continue to rise faster than overall inflation. And the labor market, while stable, has cooled from the overheated conditions of 2022 when job openings vastly outnumbered available workers. The Fed is threading a needle, trying to support growth without reigniting inflation.

The Case for Faster Cuts

Not everyone buys the Fed’s cautious stance. Zandi’s prediction of three rate cuts in the first half of 2026 rests on three arguments that challenge the central bank’s current outlook.

First, the labor market may be weaker than headline numbers suggest. Job openings have declined from their 12 million peak to around 7.7 million. Hiring rates have slowed. The quits rate, which measures workers voluntarily leaving jobs for better opportunities, has fallen back to pre-pandemic levels. These indicators suggest employers have less urgency to hire and workers have less leverage to negotiate, conditions that typically precede broader economic weakness.

Second, inflation may fall faster than the Fed expects. Supply chain disruptions that drove price spikes in 2021 and 2022 have largely resolved. Rent increases, which flow through to official inflation measures with a lag, have slowed dramatically in real-time data. Energy prices remain volatile but haven’t spiked in ways that would push inflation higher. If these trends continue, the Fed’s 2.5% inflation forecast for year-end may prove too pessimistic.

Third, political pressure on the Fed will intensify. The Trump administration has been vocal about wanting lower interest rates, and while the Fed maintains independence, the environment in which it operates matters. A new Fed chair will be selected after Jerome Powell’s term expires in May 2026, creating uncertainty about the central bank’s future direction. Some economists argue the Fed may cut rates more aggressively to demonstrate that its decisions respond to economic data rather than political timelines.

Goldman Sachs and Bank of America take a middle position, predicting two additional quarter-point cuts in 2026. Goldman expects cuts in March and June, while Bank of America forecasts June and July. Both would bring the terminal rate to between 3% and 3.25%, roughly half a percentage point lower than the Fed’s own median projection.

The Case for Patience

Other forecasters argue the Fed will hold the line or even reverse course. Morningstar’s Preston Caldwell expects five rate cuts altogether across 2026 and 2027, but that’s spread over two years rather than concentrated in the near term. The logic here is that inflation’s last mile to 2% may prove harder to achieve than its decline from 9% to 2.5%.

Core services inflation, which includes haircuts, healthcare, and other labor-intensive services, remains elevated. Wages are still rising faster than productivity in many sectors, which puts upward pressure on prices. And geopolitical risks, from energy supply disruptions to trade policy changes, could push prices higher in ways the Fed cannot control.

The new Fed chair appointment adds another layer of uncertainty. The Trump administration’s nominee has rattled markets that value the central bank’s credibility and independence. A Fed chair who signals willingness to prioritize short-term growth over inflation control could paradoxically lead to higher long-term rates as bond investors demand compensation for increased inflation risk.

There’s even a scenario in which the Fed raises rates. If inflation proves stickier than expected, or if fiscal policy changes push prices higher, the central bank may find itself tightening rather than easing. This is not the consensus view, but it’s a risk that investors should consider. The bond market’s current pricing assumes rates fall from here; if that assumption proves wrong, portfolio adjustments will be painful.

What This Means for You

For borrowers, 2026 brings gradual relief rather than dramatic salvation. Mortgage rates have already fallen from their 8% peak to around 6.1% for a 30-year fixed loan. Further Fed cuts could push them toward 5.5% by midyear if the more optimistic forecasts prove correct. That’s meaningful for homebuyers, particularly those who have been waiting on the sidelines for affordability to improve, but it’s not the sub-4% rates that defined the pandemic era.

Credit card holders will see modest rate declines as the prime rate falls. If the Fed cuts by a total of 0.5% this year, a credit card with a current 24% APR might drop to around 23.5%. That’s helpful at the margin but won’t transform your debt situation. Paying down balances remains more important than waiting for rate cuts.

For savers, the news is less positive. High-yield savings accounts that offered 5% yields during the Fed’s hiking cycle have already fallen to around 4.3%. Another year of rate cuts will push those yields toward 3.5% or lower. Certificates of deposit locked in at higher rates will mature and roll over at lower yields. The golden age of risk-free returns is ending, though savers will still earn more than they did through most of the 2010s.

Investors face a more complex calculation. Lower rates generally support stock prices by making future earnings more valuable today and by reducing borrowing costs for companies. The S&P 500’s performance in 2025 reflected this logic, with gains driven partly by expectations of Fed easing. But if inflation proves stickier than expected, forcing the Fed to hold or even raise rates, stock valuations that assume continued easing could face pressure.

Key Sectors to Watch

Technology companies, particularly those investing heavily in AI infrastructure, remain sensitive to rate expectations. Lower rates support the high valuations attached to growth stocks, while higher rates create headwinds. The sector’s performance in 2026 will depend partly on whether the Fed validates the rate cut expectations baked into current prices.

Housing presents a mixed picture. Lower mortgage rates will improve affordability and could revive transaction volume that has been depressed for two years. But home prices remain elevated in most markets, and inventory remains tight in desirable areas. The housing market needs both lower rates and more supply to function normally, and only one of those factors is under the Fed’s control.

Financial services companies face divergent impacts. Banks benefit when rates are higher because they can charge more for loans while keeping deposit rates relatively low. As rates fall, that spread compresses, putting pressure on profitability. However, lower rates also stimulate loan demand and reduce credit losses as borrowers find payments more manageable. The net effect depends on the pace and magnitude of cuts.

Consumer discretionary spending should benefit from lower rates and continued income growth. Households that have been cautious about large purchases may feel more comfortable borrowing for cars, appliances, and home improvements as financing costs decline. Retailers and automakers are watching Fed policy closely for signals about consumer capacity to spend.

The Bottom Line

The economic outlook for 2026 is cautiously optimistic. Inflation has largely been tamed without triggering the recession that many economists predicted. The labor market remains solid if not spectacular. Interest rates are heading lower, even if the pace is slower than borrowers would prefer. Growth is expected to continue at a healthy clip.

The risks are real but manageable. Sticky inflation could force the Fed to pause or reverse course. Political uncertainty around central bank leadership adds unpredictability. Trade policy changes could disrupt supply chains and push prices higher. Geopolitical events from Ukraine to the Middle East create ongoing volatility.

For consumers making financial decisions, the practical guidance is straightforward: rates are coming down, but slowly. If you’re waiting for mortgage rates to hit 4% before buying a house, you may be waiting a long time. If you’re hoping your credit card APR will drop significantly, you’ll be disappointed. The economy of 2026 isn’t returning to the pandemic era of free money and zero rates. It’s settling into something closer to normal, which after years of extremes, might be exactly what we need.

Sources: Federal Reserve, Morningstar, CNBC, iShares, Yahoo Finance.